While I was in college, the local priest got me to come along with him on his nursing home rounds and play old hymns on the broken piano in the community room. I would bang out “Great Is Thy Faithfulness” and “The Old Wooden Cross” and try to sing at the same time. The residents nodded or dozed; some hummed along. Later, when I became a parish priest, communion services at similar way stations for the aged found me jumping from prayer book to keyboard, playing “I Need Thee Every Hour.” But did I need them?

I always had a sense of having slipped into this musical role ignominiously, rather than seizing it with eagerness. My parents had made great emotional and financial investments in my musical training, but at university, with much angst, I chose another direction. It is easy to rue these decisions. I have friends now— we are all at retirement age—who look back with regret at what they chose to do, even though they have pursued remarkably successful careers, becoming doctors, academics, and leaders of organizations.

I sometimes assuage my own sense of guilt and disappointment—out-of-tune hymns for the elderly; how the musically mighty have fallen!—by the morally indulgent rationale that I was doing something “good” with my passable renderings of “How Great Thou Art” and “Make Me A Blessing.” Here, at least, I had chosen a far more righteous path than the commercially self-aggrandizing road of the professional musician that I had left behind. Or so I tell myself.

But is my thinking correct? The elderly and bereft, the poor and disowned, are no different from others in their value. “Rich and poor are both alike,” together “lighter than vanity” (Ps. 49:2; 62:9). The Church’s “preferential option for the poor” (the great phrase from the 1968 Medellin Conference) may be a proper imperative, but not on the basis of intrinsically different worth among classes. What counts is to offer the depth of God’s love to those with whom one lives. The poor are preferred only because they are “there”—or “here”—but are ignored. Put frankly, those who are not poor prefer to avoid living with those beside them. The “preferential option” works against this all-too-human reality. It’s an ascetic calling for the rediscovery of neighbors. Neighbor means, literally, “the dweller nearby.” The preferential option means: Open your eyes and share. We give what we have received to whomever we meet, wherever we find ourselves. That is, in part, the nature of what it means to be a creature of God: riding with the current of God’s outgoing love for what he has made.

The social philosopher Ivan Illich was right when he insisted that the Good Samaritan is about encounter, not social (or even ecclesial) policy. Neighbors, according to Jesus’s telling, are those we meet, in flesh and blood, beside whom God has placed us in whatever odd circumstances, unplanned meanderings, or simple communal proximities. There they are—and here are we: Give of yourself, Jesus says. The grand visions we have unfurled for ourselves—careers, vocations, investments, plans—are at best window dressing to these real rendezvous of destiny, which end up forming the actual soil of God’s field, the foundation of his building (1 Cor. 3:9). Neighbors: the substance of our lives.

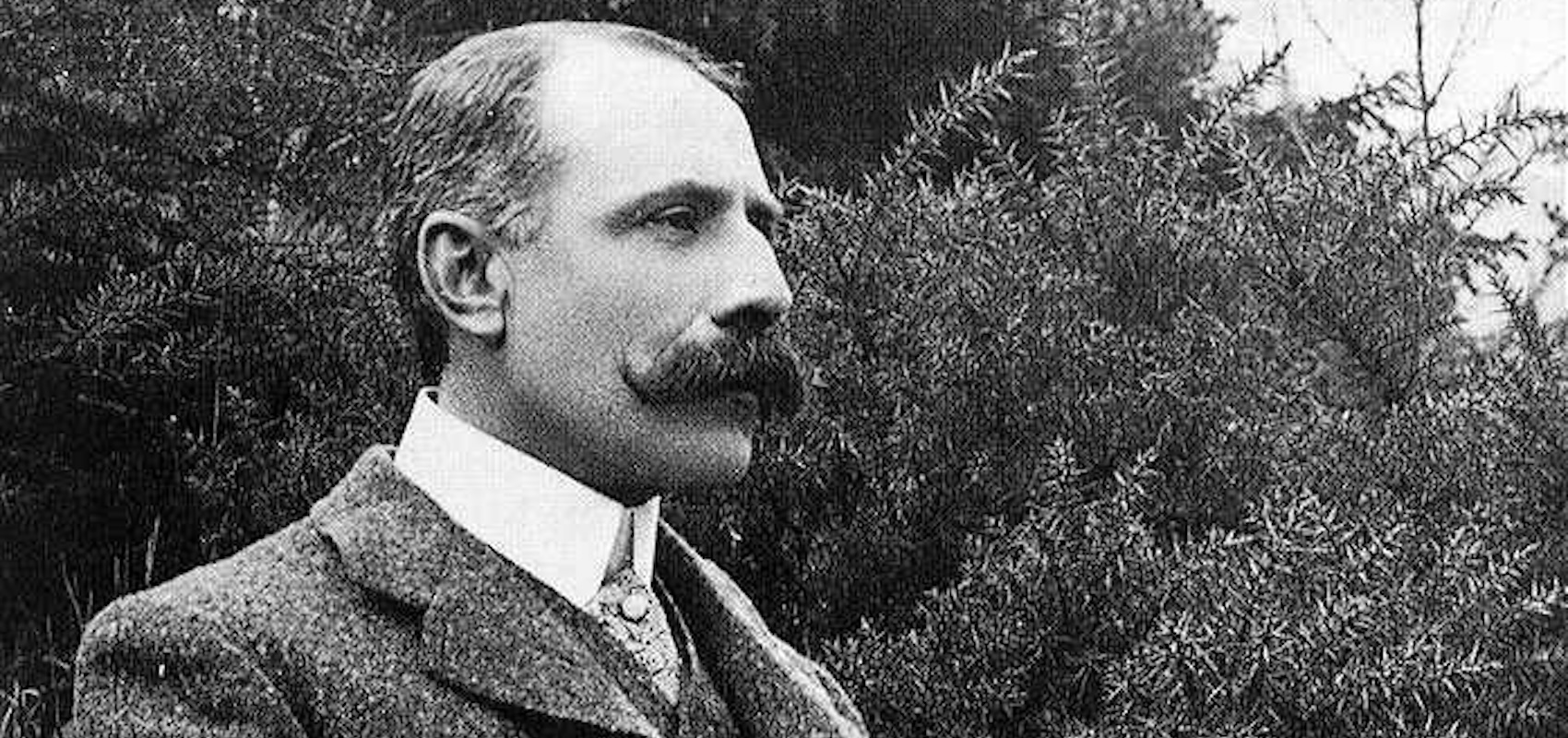

The great English composer Edward Elgar, I recently learned, spent five years at the start of his career (1879–1884) playing, conducting, and composing at the Powick lunatic asylum near his home in Worcester. The head of the institution, James Sherlock, believed that music was good therapy for the patients, and he had the asylum staff learn instruments and play for the inmates once a week, accompanying dances. Elgar was hired to write and lead these weekly events. Some of these compositions, from his early twenties, were only recently discovered and recorded.

Elgar was pursuing his own professional hopes, of course. He was of modest upbringing, the son of a musical tradesman who, among other things, tuned pianos. (The two played the violin at Powick, before the young Elgar was hired as leader of the band; an odd familial bond, perhaps, as father and son joined to entertain the mad residents.) The young Elgar worked hard to make his way as a recognized musician and composer. It was not until his forties that he gained any real—and in his case spectacularly sudden—public recognition. For years he cobbled together mostly local gigs, playing violin, composing, conducting. His years at Powick (and then at an institution for the blind) were an early part of this long apprenticeship to fame. His was a hard road known to most musicians today, though mostly without Elgar’s successful endpoint. Critics speak of the wonderful education Elgar received from his composing at Powick: adjusting to the unusual instrumentations and limited capacities of amateur players, and learning basic forms and popular styles that would later color his mostly self-taught blossoming as a renowned composer. Musical historians write as if Powick’s lost souls were most interesting as an occasion for a genius learning counterpoint.

It is unclear what Elgar thought of his years of asylum music-making. In fact, the asylum staff for whom he wrote and with whom he played were his neighbors (as were some of the patients). He would dedicate his quadrilles and polkas to individuals—clerks, nurses whom he both respected and, in the way of the local region, loved. Later, an elderly and revered Elgar would surprise unknown visitors with the introductory comment: “When I was at the lunatic asylum . . .” Proud of his origins? Of his hard work from modest beginnings? A bit. But perhaps his arresting remark mostly reflected the reality of those who had been his neighbors. You have tools—as well as dreams—and you share them with those next door. The greatest beauty unfolds and blossoms in those encounters.

Many of us have heard, even if we cannot identify, Elgar’s early violin piece, the gentle and wistful “Salut d’Amour.” The melody was used as a closing song for a celebrated documentary on the Norwegian artist Edvard Munch, himself plagued by a family history of insanity. One sister was placed in an asylum, and many who knew Munch and his own tortured emotional life dubbed him a “madman.” In 1908, Munch entered a residential psychiatric clinic and emerged the next year a calmer, if not happier, soul. The 1974 film Edvard Munch, directed by Peter Watkins, is considered pioneering in its form and production. Watkins used non- professional actors to dramatize, often improvisationally, documentary accounts, emphasizing in overlapping and often claustrophobic images and sounds the obsessive immediacies of Munch’s psyche and relations.

I went to see the film with my father in 1976, not long after the tragic death of my mother, who had long been in the grip of mental illness. The asylum had, as it were, embraced our home. Or was it the other way around? We heard Elgar’s piece at the end of the film, background to the closing summary of Munch’s nervous breakdown and the playing out of his family’s troubled journey. Elgar’s song embodies the late-nineteenth-century middle-class drawing room culture that the young Munch had moved within and from whose “bourgeois” grip he attempted to escape, perhaps without success. As the beautiful, hymn-like music played over the credits, my father and I both wept silently. Sorrow lodged in the center of our home. But the depth of that sorrow arose only because love had dwelt there first, close by, its preferred place of flourishing.

Elgar’s tune is ripe and sentimental in a classic late-Victorian way, if light in touch. It was a seemingly odd accompaniment to Munch’s story of loss, regret, and extended suffering. In fact, though, Elgar had written and presented it to his wife, Caroline Alice Roberts, as an engagement present. (She in turn had offered Edward a poem, “The Wind At Dawn,” that he later set to music.) The song is about love, and the encounter in which love, at least as we understand its human form, can only arise. “Salut d’Amour”—hello! I greet you. I am in this place, and you are, too.

I don’t know why Watkins chose to use Elgar’s piece to end his film. But what I heard those many decades ago was the greeting of love still whispered in the encounters of the mad. The Powick lunatic asylum was a place of greeting; so, too, the nursing homes down the street with their faltering hymns and the small chapels with their broken singing; so, too, the street itself with its people, whether shuffling, stooping, or striding. So too the homes along the street, however fraught with their tensions, furies, and lassitudes, the households of our first and last encounters. We change neighborhoods, move to new homes, over time. But we cannot cease, wherever we find ourselves, to stand beside someone and make music for and with them. We do need our neighbors, and they are always close by.