On November 6, 1996, Al Gore called Peter Navarro to express his sympathy. Navarro, a left-leaning economics professor at the University of California, Irvine, and Democratic congressional hopeful, had lost his race the day before. Navarro thanked the vice president and said that he’d “love to get a job in the Clinton-Gore administration.” Gore said he’d see what he could do, but apparently it wasn’t much. Navarro never got his administration job.

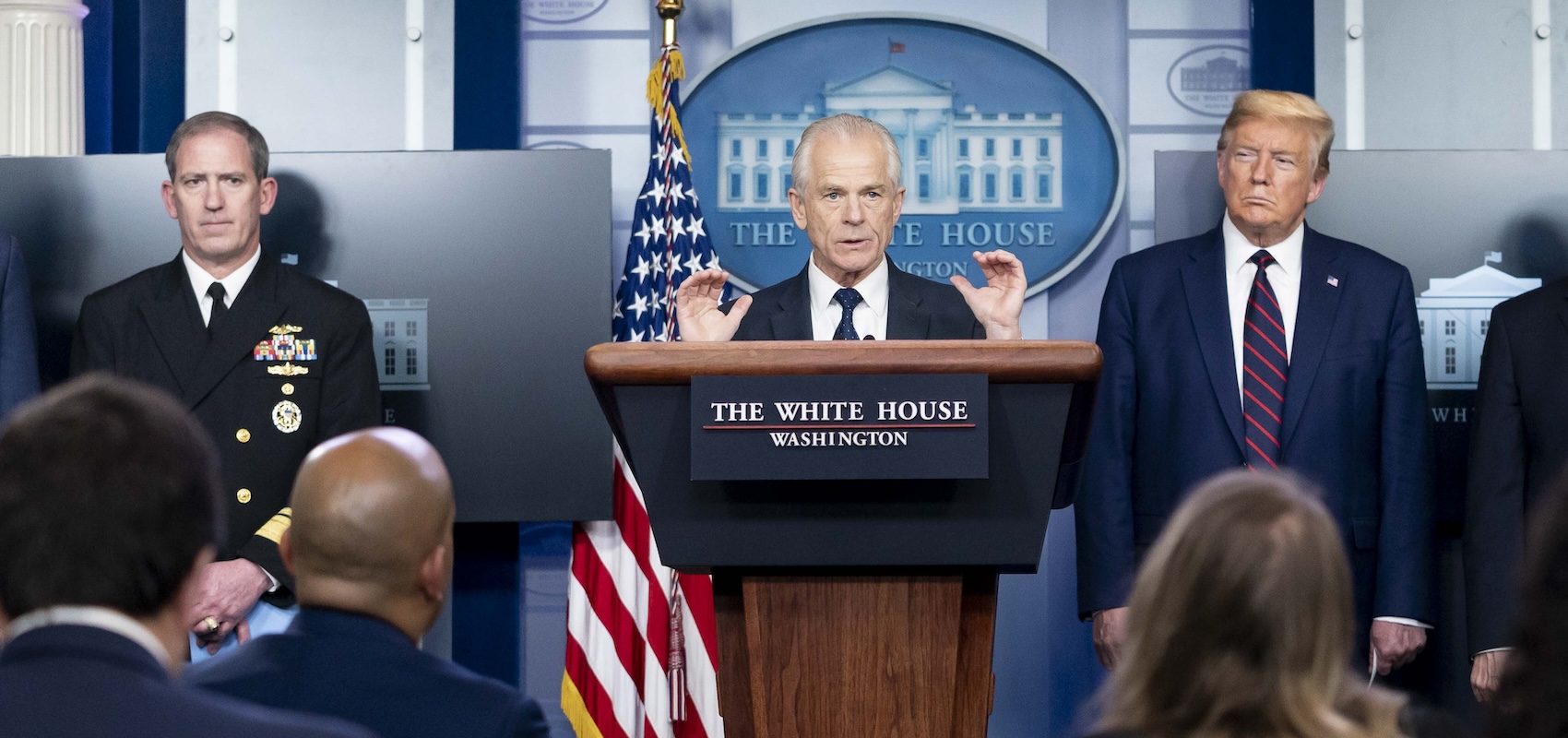

Until, that is, Donald Trump shocked the world in 2016. Navarro had signed on as an adviser to the Trump campaign, and he was rewarded in due course with a series of senior posts. In Trump’s second term, Navarro is generally credited with the tariff formulas that Trump announced on “Liberation Day.” His standing was probably boosted by the perception that he is second to none in his loyalty to Trump, having served four months in prison rather than testify regarding the failed effort to challenge the 2020 election results.

How did a liberal professor and Clinton Democrat become one of Donald Trump’s most important deputies? It is a story about changing political alignments and two conflicting understandings of the California dream—one of which stresses the creative potential of openness, while the other insists on limits. Navarro moved to California in 1986, two years after the debut of Apple’s Macintosh computer, at a moment when what we now call “the Californian Ideology” was coming into view. This outlook fused hippie social experimentation with right-wing glorification of entrepreneurship. It was also anti-statist, establishing a political pattern that would become typical of tech titans like Elon Musk.

Navarro was a proud social liberal, but something important distinguished him from adherents of the Californian Ideology. From the beginning, he insisted that government action was needed to address market failure and protect the public good. While others pursued visions of boundless freedom, he argued for limits: on urban development, on trade, on the manifold forces that he felt were endangering the America he loved. This intuition bore him inexorably toward the Trumpian right.

Navarro’s political career began in citizen activism. First as the co-chairman of a group called Citizens for Limited Growth and then as the head of a successor organization called Prevent Los Angelization Now, he argued that government action must ensure the proper development of San Diego. This conviction guided his runs for public office: for mayor in 1992, for city council in 1993, for the county board of supervisors in 1994, and for Congress in 1996. He lost each time, in most cases narrowly.

In San Diego Confidential, his self-deprecating campaign memoir from 1999, Navarro describes the threat of unregulated development: “In a free market and in the absence of planning, developers will flatten every hillside, fill every canyon, obliterate every endangered species, and pave over every wetland they think they can make a buck on.” To prevent this outcome, Navarro urged authorities to protect certain areas from development and compel developers to pay for the public facilities and infrastructure they needed for their projects.

Navarro boasted that he was “a progressive on issues such as a woman’s right to choose.” He endorsed needle exchanges and gay domestic partnerships. But he was squarer than his opponents on both the left and the right. The congressman he sought to unseat, Brian Bilbray, was an easygoing pro-choice, pro- business Republican, a surfer who had once ridden his motorcycle across the country.

Bilbray presented a conventional image of American freedom. Some of the other contenders were more eccentric. Navarro’s opponent in the Democratic primary, Nancy Casady, was a former instructor at More University, which is either a respected institution of higher education or a sex cult, depending on one’s point of view. Its members are best known for conducting a public demonstration of a woman enjoying three hours of uninterrupted sexual ecstasy, and for living in purple houses.

A dominatrix named Mistress Madison ran for the seat while seeking the nomination of Ross Perot’s Reform Party. “I believe our government should get out of our businesses, out of our bank accounts and out of our bedrooms,” she told a reporter. Perhaps the least colorful character was Dick Rider, chairman of the local Libertarian Party, with whom Navarro sought to coordinate. Rider had failed in an earlier run for office, in part because his yard signs kept disappearing. It turned out, Navarro writes, that coeds had been stealing them and hanging them in their dorm rooms.

Though hardly a conservative, then, Navarro was the only person in the race who stressed the risks of freedom over the benefits. His Republican opponent combined an embrace of free enterprise with nonjudgmental social attitudes. His Democratic opponent, a former lobbyist for California’s Abortion Rights Action League, was better known for her pro-choice bona fides than for her economic views. Mistress Madison sought to banish any limits on American eros or avarice. Despite being a socially progressive health nut, Peter Navarro had instincts that put him at odds with the Californian Ideology.

This is the through-line in his apparently erratic trajectory. The same beliefs—that markets will fail and government must intervene—that guided his anti-growth activism can be seen in his later support of protectionist trade policies. The shift in focus began in the early 2000s. At that time, Navarro writes in Taking Back Trump’s America (2022), he noticed that the ambitious young professionals who attended his evening classes were losing their jobs. After looking into the problem, he concluded that trade with China, far from being a win-win, was undermining important American industries.

Somewhere along the line, Navarro’s views on immigration shifted, as well. He writes dismissively of the issue in his campaign memoir, but in 2010—well before beginning his association with Donald Trump—he argued in The Hill that the children of illegal immigrants should not be granted citizenship.

What had changed? Trumpian populism is often associated with hollowed-out steel towns and hollers full of mobile homes. But many of the people who anticipated its central themes hail from California, a state at the cutting edge of the global economy. Their common conviction seems to be that something in the Californian Ideology went wrong, that its promises of cultural and economic openness had higher costs than many anticipated. Navarro’s protectionism is a rejection of this ideology in the area of trade. The writing of Californians like Victor Davis Hanson on the right and Mickey Kaus on the left can be seen as expressions of the same rejection in the area of immigration.

Though Navarro has never publicly renounced the social liberalism he professed in the 1990s, his arguments against free trade have taken a more conservative turn. In 2017, some members of the Trump administration were alarmed by a memo in which Navarro argued that the costs of declining manufacturing employment included “increased drug/opioid use,” a “rising mortality rate,” a “higher divorce rate,” and a “higher abortion rate.” (The liberal outlet Vox wrote of the memo, “in many respects, it’s well-grounded in recent empirical research.”) Having begun by opposing the economic side of the Californian Ideology, Navarro was increasingly opposed to that ideology’s social priorities.

Given this evolution, it is no surprise that Navarro has clashed with Elon Musk over trade policy. Navarro dismissed Musk as a “car assembler” rather than a “car manufacturer.” Musk, in turn, called Navarro “dumber than a sack of bricks.” People who share that conviction can point not only to the rocky rollout of the Liberation Day tariffs, but also to Navarro’s claims that out-and-out electoral fraud cost Trump the election in 2020. Navarro broke early with the mainstream consensus on the threat posed by China to American manufacturing. It is not clear that he will enjoy the same degree of vindication for his other heresies.

What makes Navarro important is not the details of his economic or electoral analyses, but the way he anticipated, and argued for, a broader change in political priorities. He has helped to formulate what might be called the Post-Californian Ideology—not just because it has been formulated in response to the Californian Ideology, but because it concludes that much of what made California great has disappeared. It warns that America’s pursuit of cultural and economic openness has undermined social trust and shared prosperity. It insists that the solutions to America’s problems will sometimes come from the action of the state. It recognizes that California is not only the highest expression of America’s quest for freedom. It is also the place where that quest comes to an end.