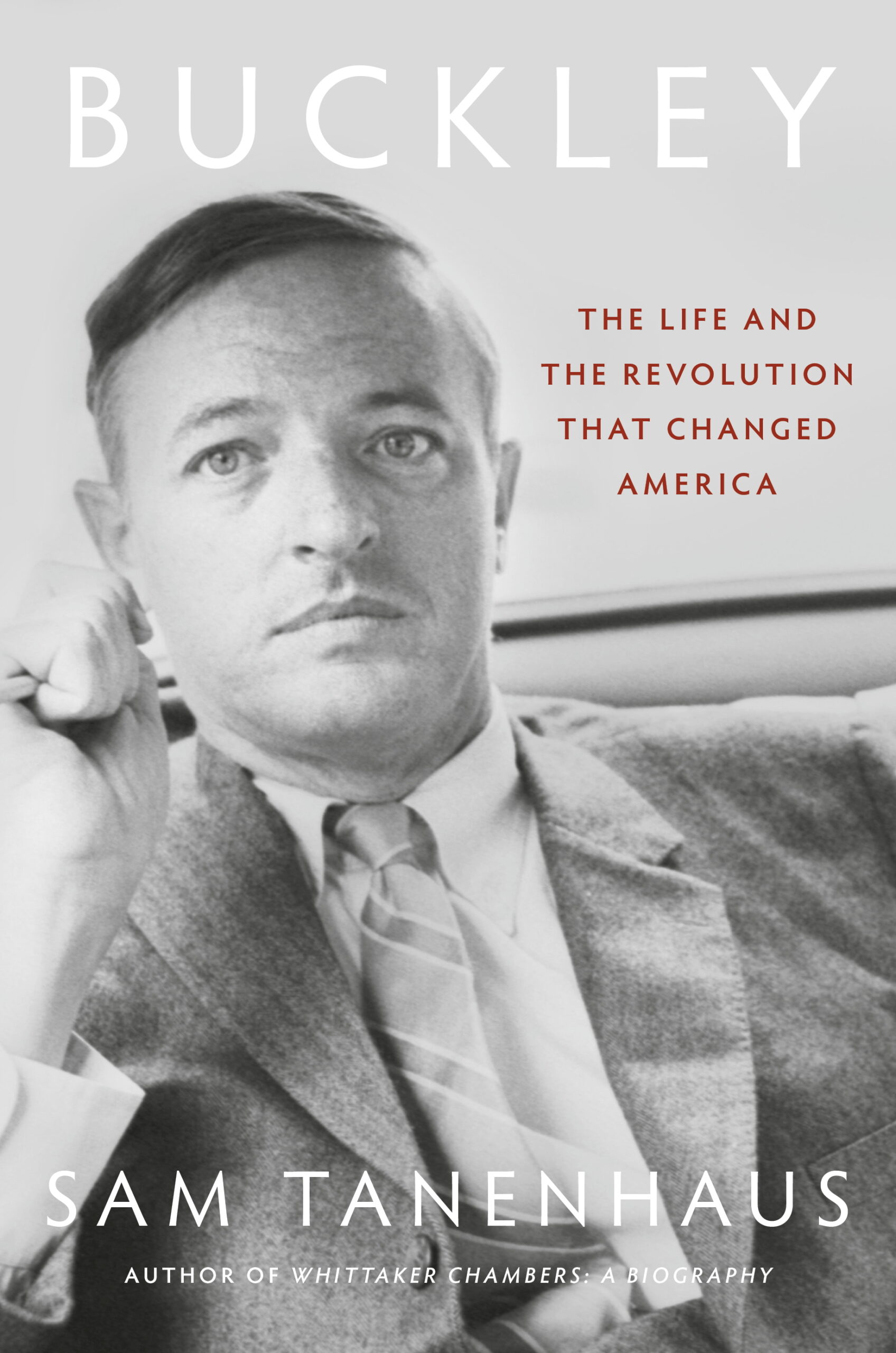

Buckley: The Life and the Revolution That Changed America

by sam tanenhaus

random house, 1,040 pages, $40

When Sam Tanenhaus agreed in 1998 to write a biography of William F. Buckley Jr., it would have been hard to name an American who deserved one more. Less than a decade after the defeat of communism, the conservative movement was so firmly in the saddle that even Democratic president Bill Clinton was extolling the virtues of deregulated markets and military strength. There had always been a conservative disposition among the American citizenry. But there had been no conservative movement worthy of the name until 1955, when the twenty-nine-year-old Yale grad “Bill” Buckley founded his weekly magazine, National Review.

Buckley not only started conservatism; for a quarter century, he embodied it. He fought campus leftism and upheld anti-communism, defending Senator Joe McCarthy and his purges in a widely read book. Wealthy, preppy, literary, he summoned dozens of less privileged activists to his family’s Connecticut estate in September 1960 to codify the movement’s principles: personal liberty, free markets, states’ rights, anti-communism.

Buckley lampooned liberal pieties in a syndicated column that was rambling, recondite, and allusive. He wrote of Hunter S. Thompson: “What emerges with a most awful vividness from this collection, presented as a chrestomathy by the most highly accredited bard of the period, is a very nearly unrelieved distemper, and this, along with the tintinnabulary drugs, is so markedly the Sign of Thompson that to fail to give it due emphasis would be to fail to remark Jimmy Durante’s nose.” Those who flocked to Buckley’s speeches would hear an outlandish Oxonian drawl, which he claimed to have picked up in a year of English public school before the war. His project was not just ideological but social: Buckley aimed to purge his movement of the losers who cost it prestige and (therefore) adherents, cutting loose the anti-Semites of the late-stage American Mercury and the conspiracy theorists of the John Birch Society. A run for mayor of New York in 1965 brought him to the attention of television producers, who would run his pioneering talk show Firing Line for four decades. Buckley counted Henry Kissinger and Ronald Reagan among his friends—one could even call them protégés. Only with Reagan’s rise to the presidency was Buckley eclipsed as the leader of the whole conservative movement.

It is true that by the time Tanenhaus embarked on his biography, there already existed an excellent one, published in 1988 by John Judis, then as now one of the giants of American political journalism. But Judis was a man of the left. Tanenhaus, soon to become the editor of the New York Times Book Review, had strong anti-communist sympathies and had written an acclaimed biography of Buckley’s friend and mentor Whittaker Chambers. That made him a good candidate to extend the story to Buckley’s death in 2008 at the age of eighty-two. Tanenhaus might take in the decades Judis missed, in which Buckley shifted his focus to spy novels and sailing the world, only occasionally descending to adjudicate intra-conservative spats over identity politics.

Though Tanenhaus enriches our understanding of Buckley’s rise, he has not supplanted Judis. Nor does his thousand-page book, published in Buckley’s centenary year, offer us a significantly more sympathetic account. Indeed, it will be seen as another milestone in an ongoing downgrade of Buckley’s writerly reputation.

Buckley was a man of parts, the scion of a family that was eccentric, peripatetic, and, to all appearances, fabulously rich. His Texas-born father had operated for years as an oil prospector in Mexico and thrilled to its culture: The ten Buckley children all spoke Spanish growing up, Bill especially well; Yale would pay him a salary to teach it when he was an undergraduate. For a while the family lived and traveled in Europe, where the children also learned French. They took riding lessons. Bill played the piano (and eventually the harpsichord). Around the dinner table in northwestern Connecticut, or at the family’s winter home in South Carolina, William F. Buckley, Sr., a charismatic and garrulous reactionary, would dominate the conversation— and his young namesake, Tanenhaus tells us, could “parrot his father’s political opinions with remarkable facility and alarming confidence.”

Chief among their preoccupations in 1940 and 1941, when Buckley was in his early teens, was to keep the United States from being drawn into another war in Europe. The country was torn between memories of Woodrow Wilson’s involvement of the United States in the First World War (widely deplored), and the power of his protégé Franklin Roosevelt in the White House (widely supported). Buckley’s father was a member of the America First movement and an admirer of Charles Lindbergh, the country’s beloved hero, who had become an earnest isolationist. Lindbergh suspected that the Jews and the British had an interest in talking the United States into war, and so did William F. Buckley Sr. There were isolationist families, like the Buckleys, and internationalists, like their neighbors the Spingarns (Jewish leftists) and the Cotters (children of the progressive Episcopalian pastor). Two of these Cotter children would become international screen stars under different names: Audrey and Jayne Meadows. Indeed, the Buckleys always seemed to be blundering into people who were destined for fame. The children competed in equestrian events with Jacqueline Bouvier (later Kennedy) and the future playwright Edward Albee. The doomed poet Sylvia Plath was wowed by the family estate when she visited it for the debut of Bill’s sister Maureen, her Smith College housemate. Betty Friedan was another Smith friend of the Buckley girls. Fats Waller once played the piano at the Buckleys’ house—his cousin was their butler.

Buckley went to Yale. He was enormously popular—tapped for the prestigious Skull & Bones club, star of the debating society, editor of the Daily News. He was so busy he hired a secretary. Under the influence of the political scientist Willmoore Kendall, a sort of right-wing Jacobin, Buckley wrote attacks on Yale’s more popular professors for the socialism and religious agnosticism they seemed to believe in. These weren’t particularly coherent arguments, and Buckley, who revered Yale, was surprised that anyone would take offense at them. The cash-strapped publisher Henry Regnery, an America Firster, was interested in publishing God and Man at Yale, the book Buckley had bundled these writings into. Buckley’s father advanced Regnery $3,000 to get the thing into print in 1951. He would provide another $25,000 when Buckley was co-writing his follow-up book, McCarthy and His Enemies, in 1954. As young Bill came under the influence of two repentant ex-communists—James Burnham, a onetime intimate of Trotsky, and the literary memoirist Whittaker Chambers—communism emerged as Buckley’s preoccupation. Through Burnham, he made contact with the CIA, for which he would work for a year in Mexico, posing as a businessman.

Tanenhaus is justified in calling Buckley’s father “an unsung founder” of modern American conservatism— through the money he poured into Buckley’s books and, later, National Review, not to mention the pre-progressive certitudes he poured into Buckley’s head. Indeed, William F. Buckley Sr. emerges from these pages as more fascinating than his son. He was rich now and then, but never the magnate he appeared to be. Buckley’s brother Jim recalled driving onto the family estate with their father and hearing him say, “If someone sees that house, they might think I have three to five million dollars.” Jim had assumed his father was worth many times that. But the patriarch was juggling, and when he suffered a stroke in the summer of 1955, the children’s $20,000 annual stipends would rapidly dwindle, then disappear altogether.

The fortunes of the senior Buckley’s company rested on connections—to authoritarian politicians in Mexico and Venezuela, to mercenaries in Mexico, and to a variety of irregular financiers in New York. He had been tied up with oilman Bernard Doheny and interior secretary A. B. Fall, conspirators in the Harding administration’s Teapot Dome scandal, which was until quite recently the most flagrant example of self-enrichment in the history of the American presidency. He was not implicated in Teapot Dome itself, but he found himself at that time “up to my nose” in a deadly counterrevolutionary insurrection in Venezuela.

The editor of National Review never knew any of this. Nor did he ever find out that his father’s father, a Texas sheriff he assumed had been cut from the same entrepreneurial cloth, had actually been a leftist revolutionary, indicted for helping the radical leader Catarino Garza escape American capture. In his notes, Tanenhaus alludes to an unpublished larger narrative he has written about this period of Buckley’s family history. One would be keen to read it.

This background helps correct a prevalent stereotype about Buckley. Because his father and his name were Irish, it is easy to assume an Irish element about his conservatism . . . something horsey, witty, and high-toned. No. Buckley was the son of a Southern frontiersman who really had more in common with an uncouth Oklahoman like Willmoore Kendall than a Merrion Square dandy like Oscar Wilde. He contrasted his own Mexican background with the Kennedys’ Ireland-focused culture. His mother was a German Catholic from New Orleans who started a chapter of the John Birch Society just as Buckley was purging it from conservatism’s ranks. He spent many of his youthful winters in South Carolina, on the estate of the magnificent Civil War diarist Mary Boykin Chesnut, which his father had bought. Buckley was straightforward, generous, hospitable, and—however proper his English—resolutely disinclined to snobbery.

Tanenhaus makes a case for regarding Bill Buckley as a Southerner; indeed, he overstates it. For three long chapters he goes into the history of segregation and the “massive resistance” to its dismantling in the 1950s. Yet Tanenhaus’s digressions, here and elsewhere, serve a point. The elder Buckley, though he treated his black employees with exemplary decency, was pouring a good deal of his fortune into the Camden News, a newspaper that backed the local Citizens’ Councils that were defending Jim Crow. Tanenhaus notes that, at Yale, Buckley opposed a plan to fund scholarships for black students and refused to sponsor an interracial dance on the grounds that interracial marriage brings “ostracism and broken bones.”

This was the attitude National Review brought to race when Buckley founded it. Tanenhaus finds it striking that it was Buckley’s mentor James Burnham, a northerner, a Europeanist, an ex-Trotskyite, who led the magazine’s opposition to civil rights. It should not surprise. The magazine’s case against desegregation was more constitutional than tribal. This has always been true of most opposition to civil rights. Tanenhaus, with a baby boomer’s tendency to use the American race problem as an all-purpose moral heuristic, calls Buckley’s editorial “Why the South Must Prevail” a statement that “haunts his legacy and the conservative movement he led.”

This was a more convincing view in 1998 than it is today. To be sure, Buckley’s own argument against civil rights was preposterously weak. For him, as long as there was the risk of one black vote tipping an election against “the claims of civilization,” blacks on the whole must be denied the franchise, because any vote could be that vote. That’s absurd: You could say the same about whites or, indeed, anyone. But stronger arguments were beginning to emerge, and in the early 1960s Barry Goldwater announced that he opposed civil rights because it would bring into being “a federal police force of mammoth proportions . . . neighbors spying on neighbors, workers spying on workers, businessmen spying on businessmen.” The woke era has vindicated Goldwater’s view.

You would need to be of Buckley’s generation, a century old, to have a sense of the countervailing pressures operating on National Review in its first decade. Its commitments cannot be deduced from contemporary ones or from Buckley’s later reputation as a reasonable member of the conservative establishment. Its starting premise was that, in drafting the hero of World War II, Gen. Dwight Eisenhower, as its presidential candidate in 1952, the Republican Party had colluded with elite “opinion makers” and betrayed the country’s conservatives. National Review intended, as Buckley put it in a private letter, to “read Dwight Eisenhower out of the conservative movement.” It ran essays by Freda Utley, another ex-communist isolationist of the Regnery circle, who thought the allies should go easier on Nazi Germany and considered Israel “the first racist state in modern history.” There was Revilo Oliver, the classicist, polemicist, and Holocaust denier, who wrote on race, heedless that war might have changed anything.

This couldn’t last. Buckley was trying to inspire the generation that fought World War II to build a political movement. They wanted to join a band of liberators, not a ward for cranks. There was a fine line here. Policing it would require of Buckley a Florentine combination of delicacy and ruthlessness. Robert Welch, the Kentucky-born anti-communist who had started the John Birch Society, had admired Buckley for years. He was a man of considerable brilliance who had never shown Buckley anything but kindness. But he saw conspiracies behind almost every event in public life. The two fell out over—of all things—Boris Pasternak’s novel Doctor Zhivago, which enraptured Buckley along with other literary Westerners when it was smuggled out of the Soviet Union in 1957. Not only was it a great novel; it was evidence of something indomitable about the Russian spirit that could survive even communism. For that very reason, Welch smelled a communist plot.

Buckley couldn’t attack the Birchers wholesale. Republicans depended on their votes. He singled out and personally denounced Welch for sins that were, in the final analysis, neither intellectual nor moral but social. “Our movement has got to grow,” Buckley explained to a friend. “It has got to expand by bringing into our ranks the moderate, wishy-washy conservatives: the Nixonites.” And to these swing voters, Welch would make the party look like what Buckley called “Crackpot Alley.” Ronald Reagan, the Great Communicator just emerging into national politics, gratefully took Buckley’s side. Buckley had assumed his own role as the movement’s Great Excommunicator.

In trying to describe what irked Buckley about Ike, Tanenhaus captures a paradox of conservative thought in a progressive world: “The New Deal had been kept intact,” he writes, “. . . through the stealth rhetoric of conservatism.” Governing ideologies are dialectical. The more progressive and planned a society becomes, the more need it has to win over public opinion, which is generally not progressive at all. So rhetorical conservatism bubbles up even in progressive eras, perhaps especially then, because progressives require something to pit against actual conservatism. This creates considerable dissension among conservatives, not to mention a lot of bad intellectual incentives.

When you consider how the establishment tried to freeze him out and how little money Buckley had at his disposal, his record of attracting genuine literary (as opposed to merely ideological) talent to his magazine is extraordinary. Early on there were prize prose stylists from the academy: the literary scholars Hugh Kenner (who had been Marshall McLuhan’s protégé in Toronto) and Guy Davenport. Joan Didion. Garry Wills. The New York Times Book Review editor John Leonard. The columnist George Will. The dance critic Arlene Croce. Almost all would break with Buckley. It was partly that they came to disagree with him politically; partly that, for a literary person, writing for a conservative magazine was the equivalent of entering a monastery; and partly that Buckley, though a generous boss, could abuse his privileges—even claiming a sort of editorial droit du seigneur by cribbing from his writers’ work before it appeared. He infuriated Wills by declaiming, unattributed, whole passages of Wills’s unpublished essay on James Baldwin during a debate with Baldwin himself at the Cambridge Union in 1965. When Wills speculated publicly (and probably baselessly) about National Review’s having been funded by the CIA, the two parted ways. Buckley complained late in life that he had been running a “finishing school for apostates.”

In 1965, Buckley ran half-seriously on the Conservative Party ticket for mayor of New York. It was a publicity stunt that changed his life. He got only 13 percent of the vote. But the race exposed him on television almost nightly, and viewers liked him—some for his frankness about problems (crime, above all), some for his quirky conservatism (he favored legalizing drugs), and some for his wit (he said that if he won, he’d demand a recount). It was here that Buckley really effected his separation from the resentful right, in a way that anticipated Boris Johnson’s campaigns for mayor of London: You cannot be dogmatically conservative when you are begging for votes in the most cosmopolitan city on earth. The public would get to see more of him. On his interview show, Firing Line, which began airing after the election, he became what Tanenhaus calls “a new type of public figure . . . a performing ideologue.” That same year, his wife Pat, daughter of a Vancouver tycoon, came into a mammoth inheritance. The Buckleys were now wealthy Manhattanites, with a maisonette on the Upper East Side, ever larger boats to feed Buckley’s growing sailing obsession, and stays in Gstaad, where every winter Buckley would ski for several weeks and write a book.

He never managed to write the book he intended to be his magnum opus—a conservative summum that he planned to call The Revolt Against the Masses. To look at the Ortega y Gasset–derived title is to see why. Even at Yale, Buckley, when he was not speaking, writing, or otherwise performing, had a tendency to get bored with politics. He had been lukewarm about all the Republican presidential candidates in his lifetime: Eisenhower, Nixon, Goldwater, Nixon again. Buckley’s youthful conservatism—which really had been a conservatism—was coming out of synch with the emerging populist movement that had borrowed the name. Conservatism as Buckley understood it was a preference for the noble against the crude, a defense of the “best that has been thought and said,” an elitist movement. He is alleged to have quipped in 1963 that he would rather be governed by the first two thousand names in the Boston phone book than by the Harvard faculty, but that was a bon mot, not a credo. He never believed any such thing. In the twenty-first century it would become a kind of conservative parlor game to ask which postwar thinkers would have backed Donald Trump’s reshaping of the Republican Party and which would have opposed it. The question can be answered for Buckley more easily than for any other: He would have been a resolute opponent. And sometime after the start of the Nixon administration he snapped awake to discover, perhaps to his private horror, that he had been having a social hallucination, and that the crowd who had been rallying behind his banner for decades, whom he had taken for Optimates, were in fact Populares.

That changed everything. How could you lead the masses in a Revolt Against the Masses? The Republican Party was now pursuing a “Southern Strategy” that focused on suburban transients and poor whites in the sticks. Those were not Buckley’s people. “Even now, the only newspaper Bill read or took seriously was the Times,” Tanenhaus tells us. Buckley was beginning to backpedal from his slashing assertions about civil rights. “I was wrong,” he eventually said of his opposition to racial integration. “Federal intervention was necessary.” Why break one’s mind over the race problem? In the European ski resorts and yacht clubs where he spent so much of the year, it didn’t really come up. Buckley was writing yachting memoirs and spy novels. He was learning to paint with David Niven, Princess Grace, Teddy Kennedy, and John Kenneth Galbraith. He came to feel a “sneaking affection” even for his old liberal-Republican nemesis, Nelson Rockefeller. Forced to choose perfection of the life or of the work, Buckley settled on the former.

Not that everybody in the establishment was willing to let bygones be bygones. Gore Vidal called Buckley a Nazi and took his languorous manner as evidence of closeted homosexuality, and was constantly getting the better of him in debate. The televised conversations the two held during the party conventions in summer 1968 turned into an embarrassment. At the height of the popularity of segregationist George Wallace, Vidal implied that Buckley, absent from the set, was a member of the Ku Klux Klan. “He’s over at that Wallace headquarters, stitching hoods,” Vidal said. Eventually Buckley lost his temper on television, calling Vidal a queer, and he insisted on writing up the incident for Esquire magazine. Vidal again bested him, using the pages of Esquire to rebut Buckley’s account by retailing stories from Audrey and Jayne Meadows—Buckley’s youthful friends and Vidal’s adult ones—about the bigotries of Buckley’s father.

Starting in the 1970s, Buckley was, socially speaking, a grandee in a party with which, sociologically speaking, he had little in common. His two closest friends were Henry Kissinger and Ronald Reagan, both of them outsiders for whose bona fides he had vouched—and whose undying gratitude he now enjoyed. Buckley had never really been a Nixon man, but now he drifted around the administration taking odd jobs. He sat on the board of the U.S. Information Agency. He spent a few weeks scrounging ineffectually for information in Chile in 1971, even traveling to the coastal retreat of Pablo Neruda in Isla Negra, though the poet wouldn’t see him. He became the U.S. representative to the UN’s so-called Third Committee, responsible for human rights—a post he happened to occupy during the Yom Kippur War of 1973.

Tanenhaus is struck at several junctures in Buckley’s life by his poor judgment and inattention to basic life matters. One episode stands out from his time running for mayor. Edgar Smith—rapist, murderer, and National Review subscriber—was on death row, convicted of biting the breast off a fifteen-year-old girl and shattering her head with a boulder. Through sheer force of flattery, he bamboozled Buckley into believing he had been framed. Buckley worked tirelessly and won his release, without—Tanenhaus shows—ever taking the trouble to familiarize himself with the basic facts of the case, including the evidence. Even after Smith plunged a six-inch knife into a woman’s chest, Buckley couldn’t see that he himself had done anything wrong.

Now in the Nixon years, Buckley seemed again at sea. When the New York Times published the Pentagon Papers, it occurred to Buckley that it would be funny to write a parody in the form of a “fake” Pentagon Papers, alleging U.S. and foreign crimes around the world. The problem was that it wasn’t funny at all. It was just a set of false reports that misled government officials and other journalists for days.

Buckley was surprised by the scandal over the Watergate break-in of 1972, which led to Nixon’s resignation two years later. His main preoccupation throughout was to protect his old CIA friend E. Howard Hunt, the organizer of the break-in itself. Buckley hid from his readers the important information he knew about Hunt, and even helped him with legal expenses. Tanenhaus judges Buckley harshly for what he sees as a grievous breach of journalistic ethics. “It was one thing to shield a source as the Washington Post’s Bob Woodward shielded his crucial FBI source, ‘Deep Throat,’ for the purpose of informing the public,” Tanenhaus writes. “It was quite another to protect powerful people from public scrutiny.”

Was it? Who fits better under the rubric “powerful people”? The washed-up, newly widowed persona non grata E. Howard Hunt? Or “Deep Throat,” who turned out to be Mark Felt, long J. Edgar Hoover’s top aide at the FBI? When it mattered, Woodward did not tell readers of Felt’s FBI connections or of his own prior acquaintance with Felt. Buckley’s role seems more, not less, defensible. He seems more like someone trying to live up to E. M. Forster’s old dictum: “If I had to choose between betraying my country and betraying my friend, I hope I should have the guts to betray my country.” It speaks well of him.

In the half decade between the fall of Nixon and the election of Reagan, Buckley found himself, in Tanenhaus’s words, “at odds with others on the right.” Since this was probably the most conservative half decade of the last century, it was an odd time to be on the outs with the movement as a whole. But once his friend Reagan was elected, he gained the relevance that comes from influence. He made recommendations for Reagan hires—including Richard Perle, Jeane Kirkpatrick, and Eugene Rostow—that give Buckley a claim to be one of the founders of what we now call neoconservatism, and celebrated the twenty-fifth anniversary of National Review.

And in this celebratory mood, with a quarter-century of Buckley’s life still ahead, the book comes to a halt. It gives the reader a few epilogue-style pages and simply skips the rest of Buckley’s life, without offering any justification. Is there one? Buckley’s last decades were, as we say, more social than political. His wife, a gatekeeper of Manhattan society in the age of new investment banking fortunes and the lavish charity balls described in Tom Wolfe’s Bonfire of the Vanities, will likely go down as a more significant fin de siècle figure than he was. Buckley was now inhabiting a world more familiar to society columnists than to political biographers.

Nonetheless, it is striking that Tanenhaus’s discussion of Buckley’s political maneuvering in the Reagan years is less detailed than the one Judis gave us a generation ago. And concerning the years after Judis wrote, there remains much to say about the way, once communism was vanquished, the Reagan coalition unraveled. Buckley played a role in that unraveling during the presidency of George H. W. Bush. National Review editor Peter Brimelow tried to reintroduce the case for a restrictive immigration policy. Brimelow would eventually leave the magazine and found the right-wing website VDARE. And two writers, Pat Buchanan and – Joseph Sobran—the former a one-time Buckley friend, the latter a Buckley protégé—waged a strident print campaign against the outsized influence of Israel’s interests on U.S. foreign policy. Buckley ousted Sobran (eventually), scolded Buchanan (then, confusingly, endorsed him for the Republican presidential nomination in the New Hampshire primary), and wrote a meandering essay called In Search of Anti-Semitism, which was nearly impossible to draw a message out of. But Tanenhaus is a smart student of ideology and could at least have tried. He gives the episode half a sentence.

The book winds up feeling like one of those three-volume nineteenth-century lives that is missing its final volume. Perhaps the explanation is simple: Tanenhaus didn’t make a curious artistic choice. He just ran out of time. Maybe he got sidetracked by the quantity of material he found on the early part of Buckley’s life, until, a quarter-century into the project, the Buckley centennial loomed, and it was time to fish or cut bait.

An ambivalent picture emerges. When Buckley was finishing McCarthy and His Enemies in 1954, he was puzzled by the mistrust of McCarthy’s protective wife, Jean. Didn’t she see that, in a world of enemies, Buckley was one of the only writers who wished him well? Of course she did. But as Tanenhaus puts it, she also “shrewdly saw what McCarthy merely sensed: that this ringing defense of her husband was littered with fastidious hedgings and muted concessions to his critics.” So it is with Sam Tanenhaus’s biography. It has brought to light Buckley’s wit, his hard work, his gift for friendship, and his extraordinary generosity, monetary and otherwise, to those he loved. Still, every hundred pages or so, Tanenhaus lets drop some damnation-with-faint-praise that gives a lukewarm, and probably accurate, account of how posterity will see him. “Buckley’s function had never been to give theoretical substance to the movement,” he writes. “He was not its best or most serious thinker. He was its most articulate voice.”