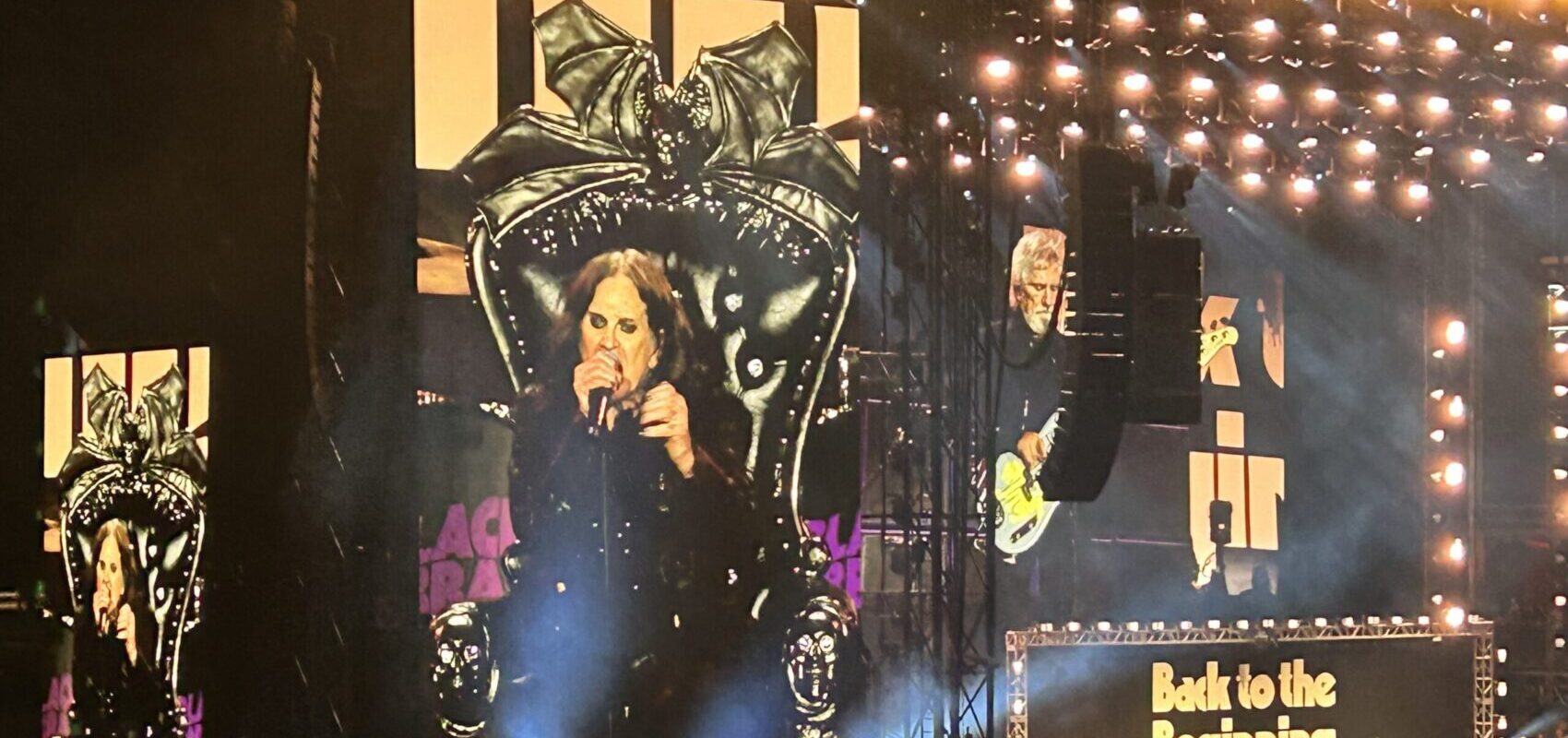

John Michael “Ozzy” Osbourne’s farewell show, performed on July 5, was explicitly patriarchal. His musical descendants—“hard” groups like Metallica, Guns N’ Roses, Tool, Slayer, and two supergroups led by Rage Against the Machine’s Tom Morello—performed at the benefit concert, held near Osbourne’s hometown of Birmingham and titled “Back to the Beginning.” More groups and artists, including Def Leppard, Billy Idol, and Marilyn Manson, filmed tributes to the aged star. The selected lineup (and who among that lineup got to play what and when) represents a conferral of blessings. Ozzy, unable to stand due to his Parkinson’s disease, was seated on a black, demon-bat throne, playing Israel speaking to his sons. Two weeks later, he died.

How ought he be remembered? Professionally, Ozzy’s music will far outlast his seventy-six years, having accrued, cumulatively, billions of listens. The band he fronted, Black Sabbath, may perform a few revival shows. Even if not, he leaves behind countless groups inspired by his music and performance. But personally, his legacy is less impressive. He had a history of violence, infidelity, and substance abuse: In 1989, during a drug fugue, he tried to murder his wife Sharon, lunging to strangle her. His offenses against those nearest to him are legion, but Ozzy has his defenders. Sharon was with him to the end, and bandmates speak of his kindness, even while recounting his abuses. Onstage he would bite, scratch, and hose down anyone who got within range. Those same bandmates played witness to his public defecation and urination. Restaurants, elevators, public monuments—nothing was safe from defilement.

Religiously, his legacy is confused.

Ozzy has long faced accusations of devil worship. But watching The Osbournes, his family’s fly-on-the-wall reality sitcom, one sees a house filled with crosses—not ironic, gothic crucifixes, but kitschy, bless-this-home decorations. Ozzy wears his cross necklace and rings when puttering around the house. It’s hard to read Satanism into the suburban setting, and he himself repeatedly denied the accusations, stating that the “Prince of Darkness” moniker was a fan-creation, that satanic imagery in his music and performances was merely performative, and that he is a Christian—a practicing Anglican, apparently. But Satanism is not defined by parish membership; one needn’t sign up for the Church of Satan’s email newsletter to cooperate with the devil.

During the baptismal vows common to Catholics, Anglicans, and Lutherans, the baptized renounces the devil, all his works, and all his pomps. Ozzy may have renounced the devil, at times, but he embraced his works and pomps. The sins for which he was infamous—including the mass-killing of seventeen cats during yet another drug-induced episode—stand alongside his dark influence on others. His songs inspired suicide (“Suicide Solution”), murder (“Bark at the Moon”), and, according to one documentary, the taunting letters of a satanic serial killer (“After Forever,” the Son of Sam). He gave a bandmate interested in the occult and Satan a sixteenth-century spell book, after which he had a demonic experience. And if making millions from songs like “N.I.B”—“look into my eyes, you will see who I am / my name is Lucifer, please take my hand”—a love song from Satan’s point of view, does not constitute embracing the devil’s pomp, what does?

John Cardinal O’Connor, referencing Ozzy in a sermon, affirmed that “some music is a help to the devil.”

The idea that someone who claims Christianity, who wears a cross necklace, might glorify the devil never seemingly clicked for Ozzy and the other members of Black Sabbath. In early interviews, the bandmates would express a degree of annoyance at questions about black magic and occultism. For their 1971 U.S. tour, they toned down lyrics and scheduled shows at a Catholic high school and an Anglican church. But at the same time, their U.S. distributor, Warner Bros. Records, allegedly hired Church of Satan founder Anton LaVey to ride on a parade float promoting the band. Lyricist Geezer Butler, himself influenced by the English occultist Aleister Crowley, has claimed it was just a LaVey impersonator, but there is a degree of nominative determinism in the affair—they were called Black Sabbath after all. Satanists would approach the band after shows and they were invited to Black Masses. Ozzy recalls telling them, “The only evil spirits I’m interested in are called whiskey, vodka and gin.” But just because someone isn’t interested in the devil—at least not liturgically—doesn’t mean the devil isn’t interested in him.

Was Ozzy demonically obsessed, subject to thoughts and urges of demonic origin? It would explain a lot. His bandmates speak of him becoming uncontrollable onstage, even to himself, though drugs and alcohol were certainly a factor. (He infamously bit the heads off of two doves after signing his first solo record deal.) Offstage, when he tried to murder Sharon, he spoke in the plural: “We’ve come to a decision that you’ve got to die.” Decades later, describing himself, Ozzy said, “I think there’s a wild man in everybody. I’m a split personality.” He suffered months-long bouts of depression in 1979 and 2012.

Of course, all of this could be attributed to the heavy drug use—no demonic influence necessary. But Ozzy Osbourne was the Prince of Darkness. Names and symbols have meaning, even to those who insist they don’t.