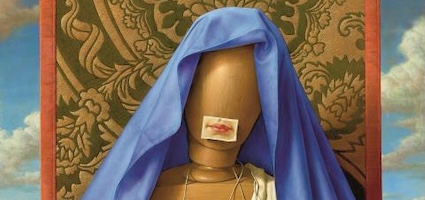

Renaissance painters would use life-sized wooden dolls called manichini to study how drapery folds on the human body. One day, a present-day German painter in Leipzig placed a blue piece of fabric over the head of such a mannequin. His dog was playing with a tennis ball and placed it in the mannequin’s lap. The painter liked the color scheme of warm ocher, white, blue, and the bright yellow-green of the tennis ball—so he painted a still life entitled Mater. The eyeless mother’s breasts are depicted as dangling tennis balls. Her mouth is painted on a piece of paper, and she presents a drawing of her infant child to the viewer. Mater is cold and lifeless, a Madonna without motherliness.

The artist’s name is Michael Triegel. He was born in 1968 in the Soviet-occupied part of Germany. It was only after the fall of the Berlin Wall that he made the “salvific” discovery that, alongside secular art, there is also art with a devotional dimension.

The green brocade cloth in the background of Mater evokes the Madonnas of Jan van Eyck or Giovanni Bellini. During an exhibition, a ten-year-old boy asked Triegel why he painted the Holy Mary like that. He asked the boy why he thought it was Mary—it was just a still life, after all. The boy replied, “That’s how Mary is always painted.” Even in the coldness of the painting, he saw the enduring presence of the Mother of God.

The painting elicited two different reactions from adults: Some considered it blasphemous, while others recognized it as a critique of a rigid and faceless church. Triegel says that he had neither meaning in mind when he painted it. However, the experience with the boy moved him almost as deeply as his first visit to Rome. There, before the high altar of the Church of the Gesù, he almost fell to his knees in awe—long before he was baptized as a Catholic in 2014.

Today, Triegel is one of the most eminent Christian artists of our time. An anachronistic pictor doctus, he confidently and unabashedly places himself in the classical, old master, mannerist, and mythological tradition of European painting. He has fulfilled numerous church commissions and has painted two portraits of Pope Benedict XVI.

Stylistically, he belongs to the Leipzig School, known for socialist realism, figurative painting, and a high level of craftsmanship. Early on, he felt an inner resistance to the spirit of the German Democratic Republic. Given that the Christian-humanist tradition was taboo in East Germany, its artistic revival through Triegel is experienced as unusual, fresh, and fascinating.

Triegel learned his time-consuming and meticulous painting technique at the Leipzig Hochschule für Grafik und Buchkunst. First, the painting surface is elaborately primed, the composition is sketched, and only then are individual sections gradually worked out in delicate grisaille tones. The many glazes create a radiant effect. Much more could be said about his paintings, such as the revolutionary Annunciation (2008), the overwhelming Deus absconditus (2013), Ideal (2014), Renaissance (2015), or his Tabula Smaragdina (2023–24). I encourage readers to look them up and ponder them.

In 2020, Triegel was commissioned to paint a new central panel for the triptych in the west choir of the famous Naumburg Cathedral, a UNESCO World Heritage Site since 2018. The original central panel, painted by Lucas Cranach between 1517 and 1519, was destroyed in 1541 during the Reformation. Triegel’s new creation fits masterfully and humbly between Cranach’s side panels and has been very well received. For the Protestant parish, the completed altarpiece is an artistic and liturgical gain.

UNESCO, however, determined that the triptych now obstructs the view of thirteenth-century statues depicting donors and benefactors of the cathedral. It demanded that the altar be moved to another part of the church and threatened to revoke the World Heritage classification. Moving the altar would mean its desecration. Moreover, the donor figures were designed to surround an altar to begin with—without an altar, their presence loses meaning. The years-long dispute highlights the all-too-familiar power struggles among European art historians and restorers, who view themselves and their secular worldview as superior to the historical or metaphysical spirit of a building.

It was recently announced that the altarpiece will be on display in Rome at the Church of Campo Santo Teutonico for two years starting in November. During this time, a solution will be sought to bring the work back to Naumburg. So the dispute will go on, but it will not stop the force of nature that is Michael Triegel. His work bears witness to three things: First, what was once possible in art is always possible. Second, classical painting naturally becomes contemporary when it’s practiced. And third, public life need not follow a path of decline. Transcendence can be found all around us—even in the eyeless face of a mannequin.