Over the last few years, I have spent a good bit of time reading the early critical theorists, including Theodor Adorno, Max Horkheimer, Walter Benjamin, and Herbert Marcuse. And reflecting on Marcuse seems especially apropos in the aftermath of Charlie Kirk’s assassination. Marcuse had made some striking statements on why the words and thoughts of more conservative and traditional folks should be disallowed. Marcuse was also clear that force might be needed to silence the words and prevent the thoughts of traditionalists or conservatives.

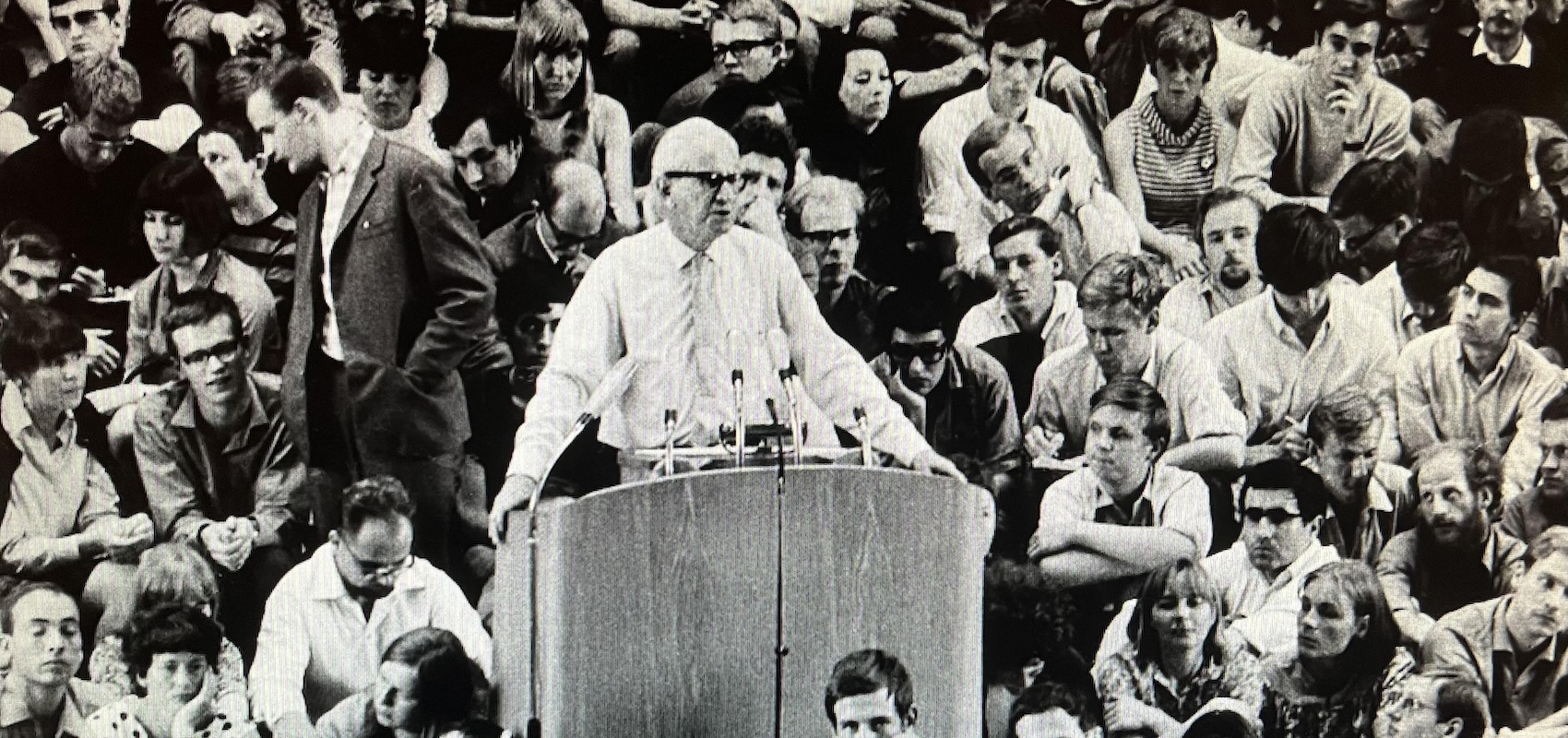

Herbert Marcuse (1898–1979) was one of the early members of the school known as “critical theory” (the Frankfurt School), and one of the most significant philosophers of the so-called “new left” during the twentieth century. In the 1960s, he reached virtual rock-star status.

He was an impressive thinker and no second-rate philosopher. He published works such as Reason and Revolution: Hegel and the Rise of Social Theory (1941), Eros and Civilization: A Philosophical Inquiry into Freud (1955), and One-Dimensional Man: Studies in the Ideology of Advanced Industrial Society (1964). He was likely the most prolific of the early critical theorists.

For critical theorists, fascism was public enemy number one. They were preoccupied with the question: How is the next Hitler to be stopped? What can be done to stop fascism—and to stop it before it even begins to develop?

Theodor Adorno developed an “F-scale” (“fascist-scale”) personality test in his co-edited work The Authoritarian Personality (1950). It was based on a series of questions used to determine who was actually a “fascist” or who might be on the path toward becoming a fascist—who, in other words, had an “authoritarian personality.” If one supported the traditional family, or believed the husband was the head of the wife, or had more conservative or traditional political values, one would score higher on the “F-scale.”

While some of the critical theorists seemed generally happy to work at the theoretical level, Marcuse was much more open to violent and revolutionary activity. That tendency becomes explicit in his classic essay “Repressive Tolerance,” published in 1965 in A Critique of Pure Tolerance (which Marcuse co-edited).

In this widely read essay, Marcuse rejects liberal notions of free speech and argues that the use of physical force to stop the free expression of ideas can be justified: “Tolerance cannot be indiscriminate and equal with respect to the contents of expression, neither in word nor in deed; it cannot protect false words and wrong deeds which demonstrate that they contradict and counteract the possibilities of liberation.”

In an ideal society in which everyone adopts a progressive outlook, we can endorse free speech. But society falls short of that ideal. Therefore, Marcuse continues,

society cannot be indiscriminate where the pacification of existence, where freedom and happiness themselves are at stake: here, certain things cannot be said, certain ideas cannot be expressed, certain policies cannot be proposed, certain behavior cannot be permitted without making tolerance an instrument for the continuation of servitude.

Marcuse’s argument goes something like this: If everyone (say, in the U.S.) was truly free and could reason and argue well, then “free speech” in the traditional sense would (or should) work. But Marcuse believed that people are indoctrinated by the inherent authoritarianism of traditional morality and the oppressive structures of capitalism such that the notion of free speech cannot be allowed. If proponents of the “unprogressive” worldview are allowed to speak, they will reinforce the indoctrination and perpetuate servitude.

As Marcuse wrote, the current political and cultural framework, the framework of “abstract tolerance and spurious objectivity,” is the factor that “precondition[s] the mind against the rupture” that would allow true understanding (read: progressive convictions) to emerge.

At this point, Marcuse becomes explicit in his insistence on the paradox that true freedom may require targeted repression. Here’s his argument: “[T]he ways should not be blocked on which a subversive majority could develop, and if they are blocked by organized repression and indoctrination, their reopening may require apparently undemocratic means.”

Marcuse then gets specific in naming who should be subjected to the “undemocratic” measures of repression:

They would include the withdrawal of toleration of speech and assembly from groups and movements which promote aggressive policies, armament, chauvinism, discrimination on the grounds of race and religion, or which oppose the extension of public services, social security, medical care, etc.

In short, “undemocratic means” might be necessary to stop people and groups who are not advocates of progressive politics.

Marcuse recognized that there is a question bubbling under the surface: Who decides? Who decides what constitutes “regressive and repressive opinions”? Marcuse’s answer:

The question, who is qualified to make all these distinctions, definitions, identifications for the society as a whole, has now one logical answer, namely, everyone “in the maturity of his faculties” as a human being, everyone who has learned to think rationally and autonomously.

Of course, Marcuse believes only he and those who think like him are “in the maturity of his faculties.” Therefore, he and his allies must erect “an educational dictatorship,” not just in schools and universities, but in society as a whole. He is forthright that in present circumstances, this dictatorship entails the “cancellation of the liberal creed of free and equal discussion,” the “withdrawal of tolerance from regressive movements,” and “discriminatory tolerance in favor of progressive tendencies.”

What is needed is a “liberating tolerance,” which—and here Marcuse flies his true colors—would mean “intolerance against movements from the Right and toleration of movements from the Left.”

Marcuse gives the appearance of loyalty to liberal principle: “[S]uspension of the right of free speech and free assembly is indeed justified only if the whole of society is in extreme danger.” But then he follows with this judgment: “I maintain that our society is in such an emergency situation, and that it has become the normal state of affairs.” In other words, absent progressive revolution, suspension of free speech is not only justified, it is required.

I doubt the young man who killed Charlie Kirk was staying up late at night wading through Marcuse’s difficult philosophical works. But in many ways, Marcuse has won the culture. He certainly won the universities, which have been practicing “repressive tolerance” for decades. For someone formed by Marcuse’s perverse argument that preserving free thought requires “an educational dictatorship,” it’s not difficult to understand both the murder of Charlie Kirk and the perverse, sad, and misguided (and at times gleeful and celebratory) responses to his tragic death.

Image by Isaactrius, licensed via Creative Commons. Image cropped.