Conflict in the Middle East brings fundamental questions about just war into the public debate. Yet the use of just war may itself need justification given the evolution of the nation-state and its contemporary means of warfare.

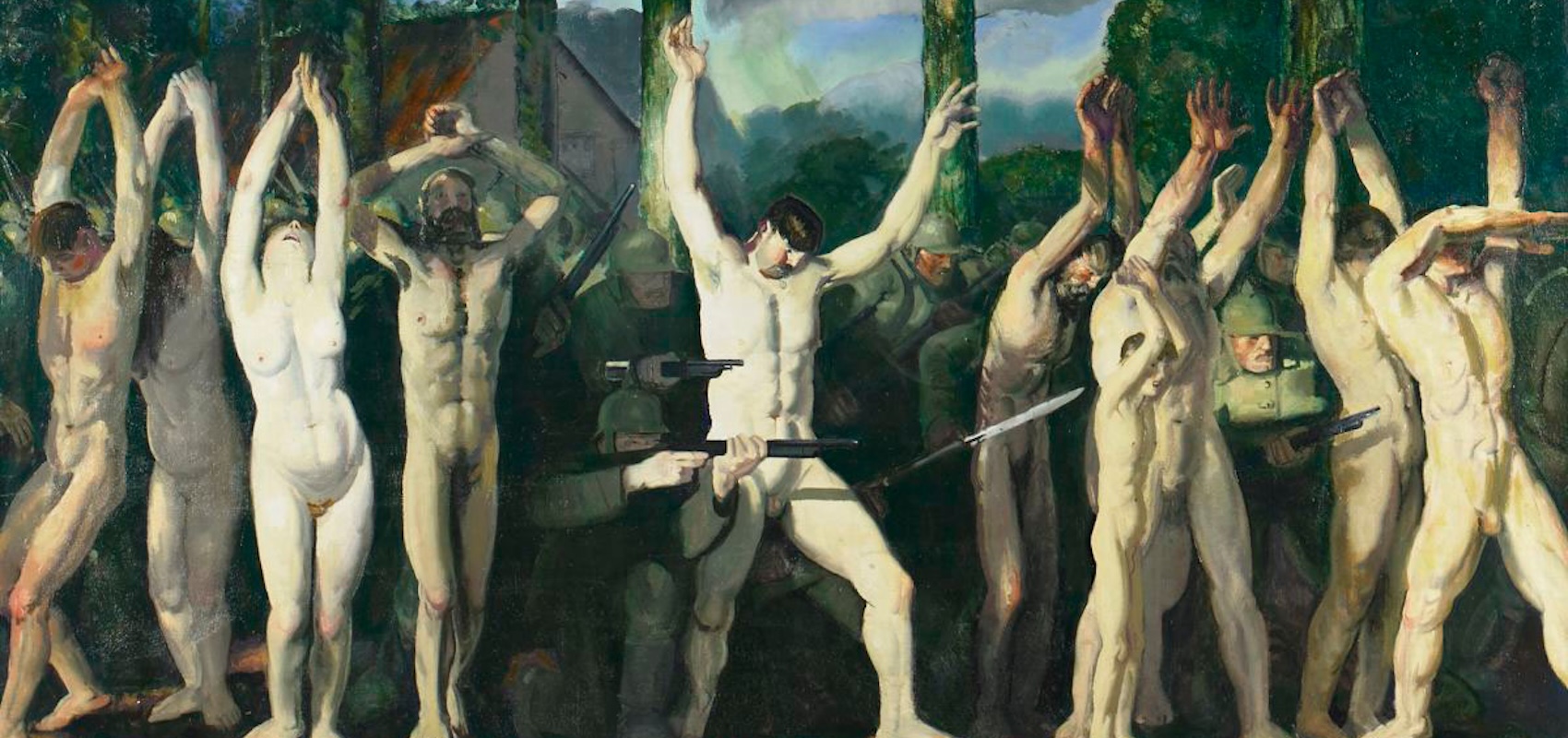

Can an ethic developed in the era of empires and overlapping political authorities—a pre-industrial ethic of war fought mainly with swords, spears, and horses—survive the post-industrial age of national sovereignty, precision strikes, and proxy wars? I argue that just war can meet the challenge, though we may need to reach farther back within the tradition to do so.

In the traditional narrative, the notion of a sovereign nation-state arose after the Peace of Westphalia and the end of the Thirty Years’ War. The Holy Roman Empire, with its convoluted influence over European kingdoms and city-states, waned in the wake of state sovereignty. But the just war ethic matured in a pre-Westphalian milieu before the era of the nation-state. Just war had to adapt to sovereignty, as seen in its later emphasis on national self-defense and the jettisoning of more traditional just war concepts like offensive punishment for violations of justice.

Still, tensions between just war and the nation-state have not been entirely worked out. Nation-states speak in the language of vital interest, not causus belli, when considering war. A vital interest, such as economic prosperity, may coincide with a just cause when threatened, yet the two are not equivalent. Sovereignty itself also presents dilemmas for just war. If sovereignty is the highest good for the political community, the question of justice is left undefined, veering towards a voluntaristic solution—I decide my own vital interests, and I may “defend” these interests as I see fit. Alternatively, just war posits a rule higher than the individual political community, a rule that both penetrates the nation-state and binds nations together. Hence, just war maintains an easy relationship with natural law (justice in war presupposes that warring states share a common morality) though a tenuous relationship with the nation-state.

Granted, the nation-state alleviates certain principles of just war, like legitimate authority. The state is now the de facto political community that can legitimately authorize war. This desire for more streamlined authority poses another predicament, however: how to deal with non-state actors, such as proxies outside the traditional nation-state, and uses of force that do not fall cleanly into conventional categories. This is where those who wish to defend just war must use the full extent of its tradition, and not merely its post-Westphalian adaptations. While not abandoning the developments of the last several centuries, it must allow potential just uses of punishment and not fear the greater emphasis traditional just war places on justice.

Moral discussions of limited strikes have never been more timely, strikes which Michael Walzer and Daniel Brunstetter call jus ad vim. Limited strikes are by their nature restrained—a nation could use more force, but limits itself to specific objectives. In the classical writings, war signifies the meting out of justice on a broad, interstate scale, whether during a limited campaign or a declared state of war. Both all-out war and limited strikes require the same justifications for killing. If a state intends the objectives rightly, proportionally, and with a just cause, the strikes may be morally permissible under the just war tradition.

The U.S. strikes against the Houthis in Yemen provide a good example. There was no official declaration of war, and the strikes were conducted intermittently over the course of many months. The cause of the strikes was in large part due to Houthi harassment of international shipping lanes in the Red Sea and the Gulf of Aden, constituting a very traditional causus belli which can be linked to both the defense of commercial ships and the infliction of just punishment on the offenders.

On the other hand, limited strikes used too frequently, particularly via air power, present a danger. Add the use of drones instead of manned aircraft, and the cost of limited strikes becomes increasingly diminished. Furthermore, the strikes’ capacity for escalation poses problems for just war, since they could do more harm than good.

Proxy wars are more troublesome since they can involve dissimulation. Yet proxy wars are not entirely new, as they precede the nation-state. The ability to hurt an enemy country without bearing the brunt of the casualties or cost is one allure of a proxy war.

For proxy wars in particular, the principle of right intention regulates many of their immoral aspects. When there is a real injury behind the fighting but for political reasons the state must fight by other means, the case is morally complicated. But if the state is merely taking advantage of a crisis to weaken an enemy, the intention is clearly unjust. In either case, it is hard to reliably judge proportionality concerns, for as Aristotle argues, we esteem little what is not our own.

Take the Houthi example again, illustrating that limited strikes and proxy wars are linked. Iranian proxies have been fighting American and Israeli forces for a long time. What is the moral difference between the nation itself fighting and the nation using a proxy to fight its wars? In traditional just war, a proxy could be classified either as an ally of a larger nation or a lesser community without the ability to satisfy legitimate authority. Morally speaking, the proxy’s actions seem to hinge on the legitimate authority in control of the proxy, which, in this example, is Iran. In a sense, then, the proxy’s actions are the actions of the host nation, either directly through a given order or indirectly through the supplying of arms. The U.S. responds by conducting restrained strikes and campaigns as a means to counter the proxies without triggering full-scale war.

When any tradition or system is forced to adapt to emerging circumstances (as all efforts of practical reason must), we must be clear about the essentials. At the heart of just war is nothing other than the establishment of justice between political communities through force. Diplomacy seeks the same outcome but through dialogue. When dialogue fails and offenses against justice recur, states sometimes turn to war. It must be stated that embracing the just war tradition does not mean we should defend war at every corner—far from it. Just war is much more restrictive than it may initially seem. But we must be clear-sighted about the world we live in and the legitimate means to achieve just ends. Do we still believe justice through force is possible today? If so, just war survives, though it may need to navigate modern means of warfare by turning back to its foundations. If not, all types of war are likely illicit, even those waged out of self-defense.