I love rural America. That love began in my formative years in Minnesota—working on a hog farm, learning to drive on dirt roads, hunting and fishing in the wilderness, and racing across the state’s trails on snowmobiles and four-wheelers. Years later, when I felt called to explore becoming a Catholic priest, I joined the Glenmary Home Missioners, whose singular mission is to serve poor, rural counties in the United States that often have no resident Catholic presence.

My ministry has taken me from the rolling hills of Appalachia to the brackish sounds of North Carolina and the fields of southwest Georgia. In each place, I’ve seen the challenges rural communities face: drug addiction, environmental damage, economic decline, and an all-too-common misunderstanding—bordering on disrespect—of rural people.

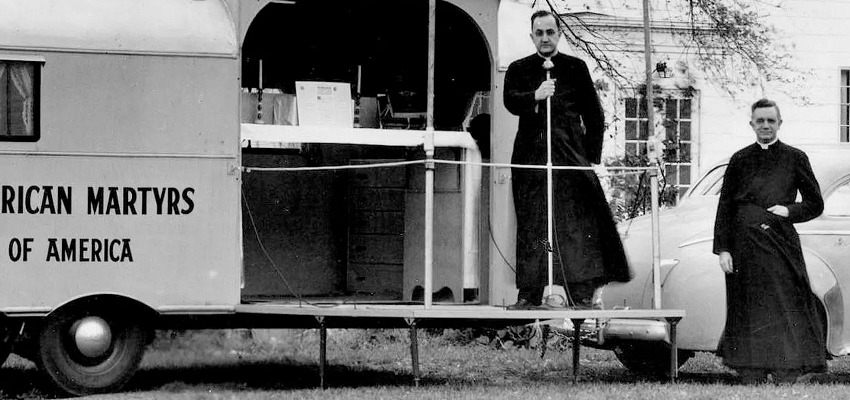

Glenmary is committed to walking with these communities. For over eighty years, our community of priests and brothers, along with lay co-workers, has worked in fourteen states, started over a hundred mission parishes, and successfully implemented hundreds of life-giving ministries. We start and run food banks, build affordable housing, tutor in struggling schools, offer drug addiction counseling, serve in prisons, facilitate faith and belonging in our churches, and much more. While others leave rural America behind, we stay.

But now our ability to serve is under threat—not from lack of will, but from the United States’ broken legal immigration system.

Like many Catholic religious communities and dioceses, and other Christian and non-Christian religious groups as well, Glenmary depends in part on members from outside the U.S. For instance, two-thirds of our members under fifty years of age are from abroad. Despite efforts to recruit Americans, the reality is that few are knocking on our doors. The men and women who come to us from other countries bring skills, faith, creativity, and a deep commitment to rural ministry. Without them, our work in some of the most underserved regions would grind to a halt.

Under recent changes during the Biden administration, it became nearly impossible for religious workers to move from a temporary visa to permanent residency. What once took months can now take decades due to administrative backlog. Those delays mean dedicated ministers—already embedded in rural towns and parishes—are forced to return home, disrupting their crucial work, and leaving others scrambling to fill the void. One of our members is, right now, packing his bags and leaving behind his ministry because he must wait for his visa to be granted.

Challenges within the legal immigration system aren’t new, and they aren’t partisan. During the current Trump administration, Glenmary has seen a rise in visa denials for vetted candidates hoping to join or remain with our community. But the reality is that, for years, overall denials for those seeking nonimmigrant visas to enter the U.S. have, in general, become increasingly common. For Glenmary, this means that our dreams to expand into other rural areas fade with each rejection, the reasons for which often seem ambiguous and arbitrary at best. This year, for the first time in recent memory, we have no new students entering formation—an unprecedented blow to our future.

Our story mirrors that of other religious groups relying on legal immigration. And here’s the irony: Many of the people we serve voted for leaders who promised to protect and support rural America—yet current policies are making it harder for us to be there.

There is a path forward. A bipartisan bill, the Religious Workforce Protection Act, now in Congress, would allow ministers on temporary visas to remain in their roles while waiting for residency. If passed, it would mean stability for ministers—both in Glenmary and in other religious congregations throughout the United States—who are already changing lives. It would also mean hope for communities that depend on them.

Even in today’s polarized climate, most Americans recognize the value of legal immigration. I see that value every day in rural parishes and towns sustained by courageous, sacrificial men and women from around the world.

I will keep working—and hoping—for the day when these dedicated ministers can enter the United States without unnecessary delay and stay where they are most needed: alongside the rural people and places I love.

The Church’s Answer to the World (ft. Carter Griffin)

In the latest installment of the ongoing interview series with contributing editor Mark Bauerlein, Fr. Carter Griffin…

An Important Civics Lesson, Well Taught

The permanent exhibit in the rotunda of the National Archives in Washington, D.C., includes original copies of…

The Lost Art of Saying “No”

Conservative pundit Matt Walsh recently contended that “we have to recapture the long-lost art of saying ‘no.’”…