The Last Supper:

Art, Faith, Sex, and Controversy in the 1980s

by paul elie

farrar, straus and giroux, 496 pages, $33

To describe the shifting relationship between religion and art, we must use the broad brush. Judaism and Islam are aniconic (image-less) religions. Christianity, an iconic religion, is the odd one out. In the Torah, the Second Commandment prohibits “graven images,” and not just of people. Portraying anything that lives “in the heavens above . . . in the earth beneath . . . or in the water under the earth” is not kosher. Muhammad omitted instructions for artists from his otherwise comprehensive code for living, but the ninth-century hadiths of Sahih al-Bukhari say on his behalf that “image-makers” will be punished on the day of resurrection for claiming to “breathe a soul” into their creations.

Christianity absorbed the pagan veneration of human images. Christians have occasionally taken the Second Commandment at its word and smashed their images—notably the Byzantine Christians of the eighth century, whose pious vandalism gives us the word iconoclasm, and European Protestants in the Reformation, whose destruction anticipated the bare interiors of modernist design. The last major episode of Christian iconoclasm I can recall was in 1966. Frenzied hordes of young Americans, most of them Southern Protestants, burned albums by the Beatles, a group of baptized Anglo-Irish Catholics.

Everyone’s a critic. The disposition to perceive harmonious arrangement and expression is innate. So is the mimetic response, the urge to create coherent, communicative objects. These impulses keep returning, from the Golden Calf to the golden mean. The aniconic religions handle them by accommodating public demand while affirming the priority of words over images and religion over art. There are lions and vegetables in the mosaics of Hellenistic-era synagogues in Israel, full-length Byzantine-style portraits on the walls of the synagogue at Dura Europos in Syria, and a mountain of portraits of Ottoman emperors and Persian wine parties, but the pictures, like the spicier imagery in the Song of Songs, are framed within the four cubits of religion. The same goes for photographs of the Lubavitcher rebbe Menachem Mendel Schneerson and Ayatollah Khomeini.

Christianity is different. Painting, sculpture, and theater became fully Christian art forms. Christianity also differed from Judaism and Islam in its concept of the earthly saeculum. As the arts began to work themselves loose from Christian supervision in early modern Europe, they became oriented toward secular patrons and emerging markets. These arrangements allowed the producers first to cultivate a secular audience, and then to declare themselves independent of any authority. A new social creature appeared. “The artist—as he comes to be called—ceases to be the craftsman or the performer, dependent upon the approval of the audience,” Lionel Trilling wrote in Sincerity and Authenticity. “His reference is to himself only, or to some transcendent power which—or who—has decreed his enterprise and alone is worthy to judge it.”

John Ruskin traced this figure’s inception to the era of Raphael and the celebrity artists of the later Italian Renaissance. Trilling dated his emergence to the Enlightenment, though this probably had less to do with philosophy than market forces and copyright laws. Either way, the decoupling of religion and art decoupled the sign from its signifier, and without always reuniting them in the social world. The watershed artwork might be Giorgione’s Tempesta (1506–08). It looks great, but no one knows what it’s about. Perhaps Giorgione didn’t know.

This uncertainty would not surprise Paul Elie. The Last Supper describes itself as an attempt to examine “crypto-religious” art in the 1980s. The art is mostly paintings, songs, and movies, though novels and poetry appear here and there. The focus is on New York City, which was the capital of the art and publishing worlds, a key stage for popular music and gay life, and hence a battleground in the culture war between gay artists and the Catholic hierarchy in the decade of AIDS. The task of the rearguard action fell to John Cardinal O’Connor.

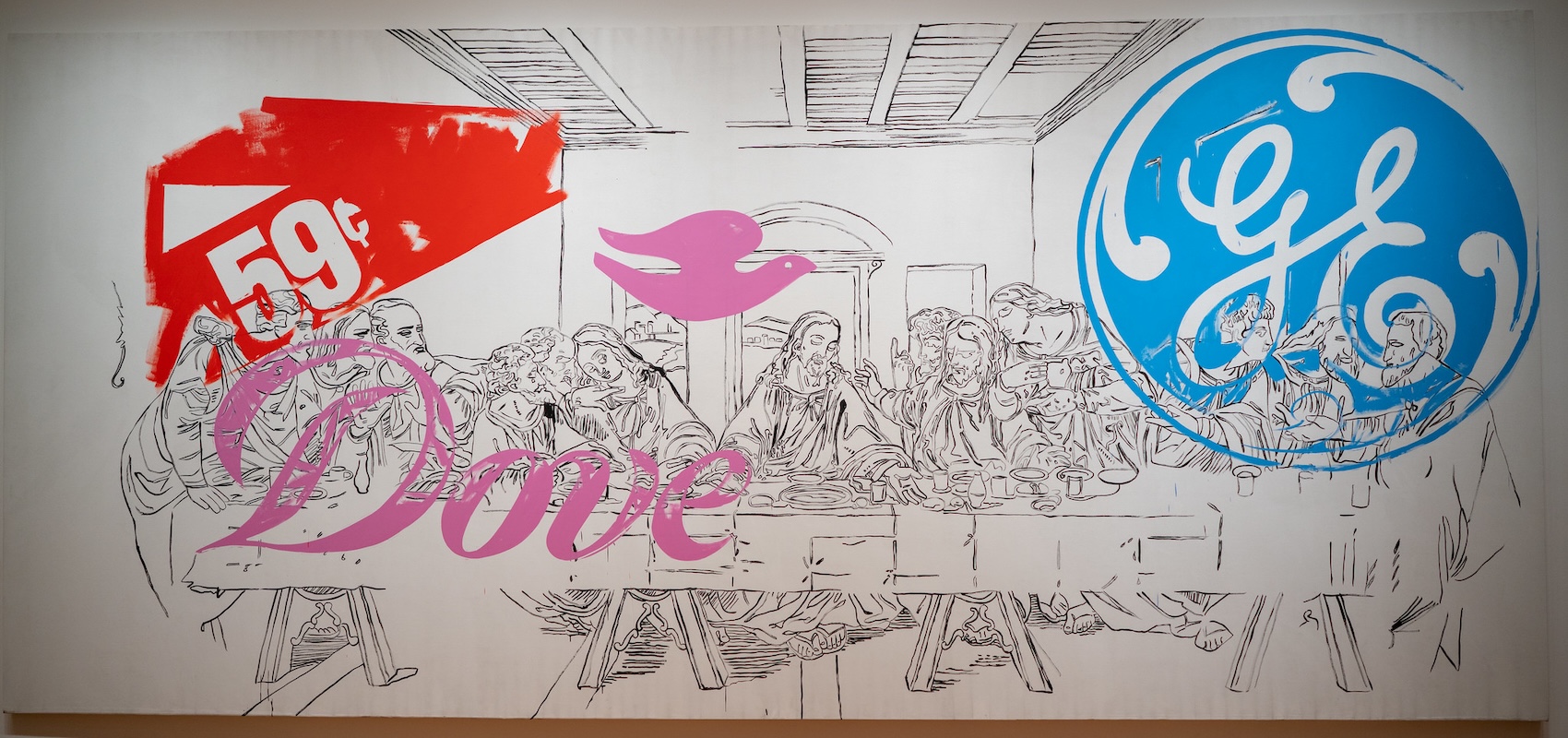

Elie’s “crypto-religious” artists are mostly of Catholic extraction. Most of the works that interest him carry Catholic connotations, autobiographical and theological. Some are explicit—for instance, Andy Warhol’s “Last Supper” series (1984–86), in which Warhol reprinted Leonardo da Vinci’s painting; Martin Scorsese’s 1988 adaptation of Nikos Kazantzakis’s 1955 novel The Last Temptation of Christ; or the MTV-powered rise of Madonna to what the language of publicity calls “iconic status.” Others, such as Robert Mapplethorpe’s gay S&M photos, were by Catholics with a grudge.

An icon is a symbol standing for the real thing, intangible though it may be. The semiotic distance is narrow in a church—and narrowest in Eastern churches, where icons are venerated as possessing in a mysterious way the sacred realities that they represent. But the semiotic distance is widened by the marketplace. Many of Elie’s artists and works descend, like the imagery in a Madonna video, from organized religion, but their adult personalities and works are products of disorganized religion, the subjectivity that Bruce Springsteen, with typical articulacy, called “that searchin’ thing” that’s “like, religiously based, in a funny kind of way. Not like orthodox religion, but it’s about basic things, you know?”

We do. Madonna released her debut single, “Everybody,” in 1982, exactly a century after Nietzsche detected the death of God. The long contraction of institutional religious authority opened the semiotic field for the spiritual countermoves of the “Me Decade” of the 1970s: evangelical revival and post-Christian searching, therapeutic idealism and cultish disorder. In the 1980s, the semiotics of icon-making scrambled into a heap of gleaming images. We got “searchin’ things” such as the band U2, another act whose endurance and popularity suggest civilizational senility.

U2’s guitars and drums echo through vast halls of reverb and delay. The lyrics are studiously vague passion plays, delivered with implausible seriousness. Like the theatricals of Madonna, who, Elie claims, “made the sports arenas of Europe her pulpit,” U2’s music makes the audience “a giant congregation, drawing together the energy of revival, rock show, football match, and political rally.”

None of these acts was “crypto-religious.” Their religiosity was explicit. Elie takes his hermeneutic from the Polish-born poet Czeslaw Miłosz. “I have always been crypto-religious and in a conflict with the political aspects of Polish Catholicism,” Miłosz wrote to the Trappist monk Thomas Merton in 1951. In Miłosz’s poem “1945,” the artist is the “descendant of ardent prayers, of gilded sculptures and miracles.” He stands “alone with my Jesus Mary” against the “illusions” of modernity and its “flat, unredeemed earth.”

Crypto-religious artists of the 1980s, Elie writes, had to “create new patterns of reverence.” The “golden hue” of Andres Serrano’s “Piss Christ” (1987) is suffused with “a touch of the apocalypse,” and the tilt of the crucifix suggests “windswept, earthshaking drama.” This legacy of “Serrano’s Catholic experience” in the Brooklyn churches of his boyhood was received ecstatically in downtown Manhattan at a time when the scene was “ravaged by a disease transmitted through bodily fluids” and the city “riven by religious strife over the body and its claims.”

Serrano was embraced by the critical crowd and praised as a provocateur. So was Robert Mapplethorpe. They did not stand alone, as Miłosz had in the interregnum between fascism and communism. Nor did Warhol, Madonna, and U2. The big names of the eighties were illusionists of modernity, flatteners of transcendence, bringing heaven down to earth and selling it wholesale. They dealt in multiples: prints, photographs, vinyl, CDs, radio mixes and remixes. They capitalized on a business model whose rules of outrage were clarified in the 1960s. That business attained peak commercial coherence in the years that Elie studies: between the advent of MTV in 1981 and the breakout of the commercial internet in the mid-1990s.

There was nothing “crypto” in the rejection of Church authority by Catholic artists such as Serrano or Sinéad O’Connor, or in the Catholic motifs in the films of Martin Scorsese. It doesn’t get more literal than squirting vials of urine onto a crucifix or making a heretical movie about the life of Jesus—or than the sex-and-religion psychodrama of the promiscuously Protestant Prince, whose music, Elie writes, “is a reminder of how much like music religion is.”

Not much cryptography is required to decode Catholics of the “searchin’ school” either. It was in the 1980s that Bruce Springsteen succumbed to the last temptation of celebrity and expanded his inter-song banter from its 1970s mode (mumbling in the manner of De Niro’s Johnny Boy character in Mean Streets) into extended secular sermonizin’ about the kind of banal and basic things that U2 was also shopping around the stadia. Even Bob Dylan, the most cryptic lyricist of the age, returned to literalism for the first time since 1964 on the three albums that followed his conversion to evangelical Christianity in late 1978 or early 1979.

The literalism continued when Dylan switched back and made the first overtly Jewish identification of his career. The artwork for 1984’s Infidels showed Dylan wearing kippah, tallit, and tefillin at the Western Wall for his son Jesse’s bar mitzvah. The first single, “Neighborhood Bully,” was a defense of the State of Israel, and as straightforward as an allegory can be. Elie believes that its lyrics “faulted the foreign-policy aims of Israel and the Christian right.” That is literally nonsense.

Elie is more interested in biography and culture-war iconography than in the quality of the artworks or whether the artist really is autonomous in Trilling’s sense. Not since Wagner packed them in at Bayreuth had sex and death been conjoined so explicitly. So why was little art of enduring merit produced in the 1980s? None of Elie’s downtown favorites amount to much in the critical rearview. Warhol had not produced anything of interest in decades. Wim Wenders was boring. Keith Haring was untalented. Sinéad O’Connor and Patti Smith were limited singers and second-rank songwriters whose biggest hits were covers. The William Burroughs chorus acclaimed Jim Carroll, but he came and went without producing anything of note. Robert Mapplethorpe was Tom of Finland for snobs. And Tunnel of Love was rubbish.

In America, MiŁosz detected “an indifference to basic values,” especially on campus, and the “subversion of the ethic of the working class, which was God, my country, my family.” The causes, Miłosz said, could be traced back “infinitely,” but the effects reflected a “very powerful transformation as far as religious imagination is concerned.” Civic piety was declining because the human image was being stripped of its “religious dimension.” The growing “difficulty of translating religion into tangible images” was also a transformation within religion and part of a fundamental social shift.

In the 1980s, you could buy albums on cassette, vinyl, or CD. It was a decade in which the social codes overlapped, too. Elie calls it the end of one era and the start of another. American society was becoming less homogeneous and more secular, but it was still possible to draw crowds by staging an old-style Kulturkampf and provoking John Cardinal O’Connor to complain about blasphemy. Disordered religion was established as the new church of the liberal upper-middle class, but the conservative lower-middle class turned evangelical and Reaganite. That spiritual reordering of old antagonisms announced a new era of intensifying hostilities—our era.

The outgoing age, Elie argues, was the world of Andres Serrano’s childhood, traditional and communal. The incoming age was “postsecular”: atomized, identitarian, and therefore increasingly religious. The characteristics are recognizable, though it is worth adding that we might now be in a period when the searchin’ and findin’ is leading to reaffiliatin’ among the young. And we should remember that, as Elie argues, the outgoing secular age was itself susceptible to religious voices, whether cryptically in the redemptive passion of “progressive social revolutions” or explicitly in the political rhetoric of Abraham Joshua Heschel, Martin Luther King Jr., and the Berrigan brothers.

The publication of Salman Rushdie’s The Satanic Verses in 1988 was the last significant literary event in America, and not because it was a great book. Elie argues that “the novel’s central challenge was a crypto-religious one,” but there was nothing “crypto” or even cryptic there. Rushdie was a secular Third Worldist, so he never made a Miłosz-style argument for rescuing a hypothetical spirit of Islam from Islamic institutions. In life and fiction, Rushdie made clear and calculated arguments for art’s rights over religion. It soon became clear that he had miscalculated.

Blasphemy was back. Riots, murders, and death threats ensued. Islam’s aniconic tradition imposed itself by force. A new age of literalism began. The liberals split. Most of the older writers defended Rushdie’s right to free expression on artistic grounds. Norman Mailer called the fatwa the “largest hit contract in history.” The lion and the lamb shared the spotlight at a pro-Rushdie PEN rally when Leon Wieseltier (Jewish, pro-Israel) joined with Edward Said (Christian, not big on Israel, but also not, as Elie thinks, an adviser to the “Palestine Liberation Authority”) to support Rushdie, an Indian-born Briton who was what some would now call “post-Muslim,” with words that—encouraging as Rushdie may have found them while he became the underground man of the age—meant nothing.

Others sided with the complainants. Roald Dahl called Rushdie a “dangerous opportunist.” A similar prickliness about presumptuous immigrants rocking the boat and the literary hierarchy can be detected in John le Carré’s response: “There is no law in life or nature that says great religions may be insulted with impunity.” Jimmy Carter, then in the prime of his fatuous ignorance, accused Rushdie of “defaming” the Qur’an and “vilifying” Muhammad. John Cardinal O’Connor deplored threats of terrorism but called Rushdie’s novel “insulting and insensitive.” Elie, for whom O’Connor is the villain of the piece, calls this “the higher ignorance.”

The battlelines of the culture war shifted into their current alignment, with America now one front in a global conflict. When Elie argues that “Islam in American public life is still typed as peripheral and cryptic—as gay life was a decade earlier,” you get the impression that he is trying to limit the controversy over what can and can’t be said to the local and manageable. It isn’t. It wasn’t in the decade of Live Aid, when the pop stars of America sang “We Are the World” in a humanitarian foretaste of 1990s triumphalism. Lou Reed and Leonard Cohen both saw this at the time, but Elie skates past them.

Reed appears in the crowd scenes of The Last Supper, including on the crowded stages of the tedious caravan of post–Live Aid charity concerts. Elie never considers him in any detail, though Reed’s 1989 album New York touched on most of Elie’s motifs: Warhol world, AIDS, gay life, the unraveling of American society (“Last Great American Whale”), the withdrawal of religion from public life (“Busload of Faith”), and even the scandal of Pope John Paul II’s receiving the newly elected Austrian president Kurt Waldheim, who really had been cryptic about his wartime service in the Wehrmacht and his role in deporting Greek Jews to Auschwitz (“Good Evening, Mr. Waldheim”).

Meanwhile, Leonard Cohen’s “The Future” (1992), a real crypto masterpiece in the Miłosz sense, is barely mentioned. The band plays a 1970s groove reminiscent of J. J. Cale. It is oddly jaunty in the way of an empty fairground ride, but the musicians sound exhausted. The cultural revolution of the 1960s is played out. The future is chaos. The “breaking of the ancient Western code” will produce a new kind of aniconic blindness, in morals and semiotic meanings. “I have seen the future, baby,” Cohen sings, “and it’s murder”:

Things are going to slide in all directions

Won’t be nothing you can measure anymore

The blizzard of the world has crossed the threshold

It’s overturned the order of the soul

“Repent, repent,” the gospel chorus chirps.

“When they said repent, I wondered what they meant,” Cohen replies. He might have had Mapplethorpe in mind when he wrote lines such as “And now the wheels of Heaven stop, you feel the devil’s riding crop,” and “Give me crack and anal sex.” Cohen certainly saw what the 1980s really were: the last, lazy decade of old certainties, of the Berlin Wall and “Stalin and St. Paul,” of a box office thriving on a theater of rebellion in which all the pistols fired blanks. This nostalgia for contained controversy shapes Paul Elie’s reconstruction. It is not wholly true to its time, and it is false to ours.

Image by Nan Palmero, license via Creative Commons. Image cropped.