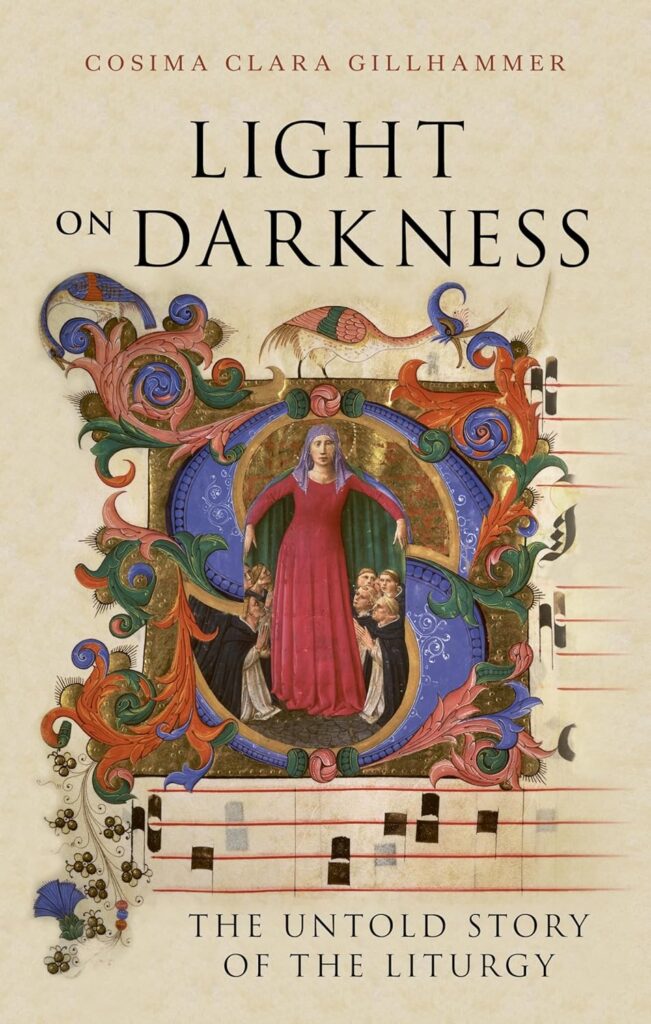

Light on Darkness:

The Untold Story of the Liturgy

by cosima clara gillhammer

reaktion, 256 pages, $25

Light on Darkness restores liturgy to its place at the heart of the medieval world. Like a Jesse tree, its trunk sprang from roots in the deep soil of antiquity, and its branches reached toward every corner of the heavens. When we read any writer of the Middle Ages—poets, theologians, historians, philosophers—we read words shaped by the liturgy of the Church. It was the common experience of every Western Christian, be he king or knight, priest or peasant. Those who knew Virgil and Cicero, those who knew Duns Scotus and Augustine, those who knew Burnt Njal and Egil Skallagrimsson, and those who knew no more than the half-pagan folklore of their homes, all knew the Mass in its seasons and variations. The liturgy was the chief form in which they encountered the faith they all professed.

In this book, Cosima Clara Gillhammer—an Oxford scholar of Middle English—explores how the medieval liturgy structured and held both the great story of salvation and the particular stories of individual lives, joining the one to the other in words, music, and movement. As she writes in the Introduction: “Funerals give a shape to mourning just as weddings give a shape to joy.” We read—reproduced in full, not merely in quotes—familiar liturgical texts such as the Reproaches and the Exsultet alongside those we now know chiefly from music, such as the Dies Irae and the Stabat Mater, and medieval poems most of us have never encountered before. Arranged by emotions and experiences—hope, suffering, grief, and so on—the book illuminates unsuspected depths of feeling: “The liturgy is not merely a set of abstract and symbolic words and gestures, but an act that engages with the whole breadth of human emotion. It reaches to the bottom of human experiences because it is an expression of the belief that God himself experienced them during his life on earth.”

These comments are reminiscent of a point made by Church historian Christopher Dawson about the liturgy’s legacy. Speaking of Renaissance humanism, he wrote: “Humanism was, it is true, a return to nature, a rediscovery of man and the natural world. But the author of the discovery, the active principle in the change was not the natural man; it was Christian man—the human type that had been produced by ten centuries of spiritual discipline and intensive cultivation of the inner life.”

The liturgy was the principal means of that cultivation, weaving together the feasts of the Church, the cycle of the earthly year, and the great events of individual lives into one seamless tapestry of observances. Gillhammer’s book centers more on feasts than, as theologians tend to do, on the structure of the Mass, for the simple reason that feasts loomed larger in medieval experience. For us, a feast is a Mass with different color vestments, which, if we’re very lucky, won’t simply have been moved to the nearest Sunday. In the Middle Ages, a “holy day” meant, in addition to its religious significance, at least a day and a half off work. There might be a vigil fast, a procession, a series of civic ceremonies. The whole of ordinary life was suspended to mark the feast, and the year contained dozens of such holy days.

The liturgical element of the celebrations was much more varied. The Divine Office played a far larger part in the lives of lay Catholics than it does now, when its communal celebration is confined primarily to religious orders. The best modern analogues are Anglican cathedrals. There, the services of Matins and Choral Evensong are at the heart of the liturgy, a time-hallowed ministry of music and beauty that draws more people annually than any of the churches’ official missions. There, as in the medieval Church, you will hear the canticles (Magnificat, Nunc Dimittis, Te Deum, and so on), the versicles and responses, the OAntiphons, and the Psalms. A devout Catholic could easily live a lifetime without hearing any of these except a rather limited selection of the Psalms, their fullness truncated and their beauty lost in translation. Lost, too, are the Stabat Mater and the Dies Irae, cut from the liturgy by reforming councils. Tenebrae is rare outside religious houses. Only the Good Friday and Easter Vigil services still retain a sense of the splendor that once accompanied feasts we now barely notice: St. Luke the Evangelist, St. John the Baptist, St. Michael and All Angels.

The proper celebration of feasts extended far beyond services, shaping the cathedrals themselves. At Wells, passages were built into the west front to allow choristers to sing from on high, their voices floating down as if angels in heaven were joining the service. At Salisbury, which was never a monastery, a huge and soaring cloister allowed the numerous processions specified by the local Sarum Rite to be celebrated in all weathers. In December, boy bishops and canons would be elected from among the choristers, exercising control of the cathedral until Holy Innocents’ Day, and embarking on visitations afterward (this tradition is one of the few omissions from Gillhammer’s book). At Corpus Christi, in addition to the processions some of us still know, townspeople would dramatize the whole of salvation history in the Mystery Plays.

Gillhammer roams well beyond the strictly liturgical (a concept that would mean rather less to the medieval mind than to the modern). We are introduced to a dialogue between Christ and his mother and poems in which an individual soul talks to Christ. We travel to Paradise with Dante and experience the Apocalypse with William Blake. In a particularly memorable chapter, we follow the musical motif of death (the opening plainchant line of the Dies Irae) from a Dark Age monastery to the Great Rift Valley, Tatooine, and Mordor, with contributions along the way from Mozart, Mahler, and Rachmaninoff. We see how potent and fertile a source of meaning the liturgy can be, even in secular settings. We also see how our sense of death has drifted over the centuries, without ever losing the archetypal sense of dread, which Duffy identifies as integral to the human experience.

I came away from the book with a sense, chiefly, of sadness, a feeling best expressed by Matthew Arnold’s “Dover Beach”:

The Sea of Faith

Was once, too, at the full, and

round earth’s shore

Lay like the folds of a bright girdle

furled.

But now I only hear

Its melancholy, long, withdrawing

roar . . .

In six years as a cathedral chorister in the Church of England, first at York Minster then at Wells, I encountered almost all of the liturgy Gillhammer explores, and more. I sang through the book of Psalms several dozen times. To this day, they are written on the heart, and verses come to mind at a moment’s notice. I knew Evensong and Matins, with their various canticles and collects, by heart. I sang the Advent Responsory in total darkness and the Te Deum in morning sunlight. I felt the urgency of a medieval Doom in the music of a nineteenth-century Requiem: Libera eas de ore leonis! Libera eas de poenis inferni, et de profundo lacu! I saw the Mystery Plays twice, once on wagons as they would have been performed in medieval times, and much later, unforgettably, on a huge banked stage in the nave of York Minster. Aside from the Easter Triduum at the Oxford Oratory, I have never met liturgy in the Catholic Church with the range, variety, or depth of feeling that I grew up with, and that Gillhammer describes.

Feeling is neither an unfortunate side effect of liturgy, nor a poor second to correct ecclesiology. A liturgy, or indeed a church, that doesn’t allow room to express the full range of human experience will be abandoned for something that does. Writing of changes to the funeral service after Vatican II, Eamon Duffy remarked:

One of the principal functions of liturgy is to allow us to pray all our thoughts and feelings, to acknowledge before God what we really are, not to suppress and sanitize our innermost selves and only bring to him what is acceptable and theologically correct. The bitter note of protest is surely one of the most basic of human responses to death, and one of the most legitimate…echoed in the cry from the cross, “Why have you forsaken me?” and elsewhere. We need to come to the knowledge that “my redeemer liveth” but we need also to be allowed to rage against the dying of the light. The old liturgy made space for both: the new does not.

In just this vacuum, this refusal to allow room for old terrors and dark feelings, a cult such as Santa Muerte can grow strong. It flourishes on emotional ground that the Church neglects.

The Psalms became the backbone of the medieval liturgy precisely because they met that need. There is a Psalm for every fear, every feast, and every feeling. Christ’s despairing cry from the cross is from the opening verse of Psalm 21/22. The poetry of the Psalms, like all truly great poetry, renders an individual experience universal. We are joined to God in moments of blackest despair: “But as for me, I am a worm, and no man; a very scorn of men, and the outcast of the people” (Coverdale, 22.6); of yearning: “Like as the hart desireth the water-brooks: so longeth my soul after thee, O God” (42.1); of wonder at Creation: “Praise the Lord upon earth: ye dragons, and all deeps/Fire and hail, snow and vapours: wind and storm fulfilling his word” (148.7–8); of exaltation: “Praise him upon the well-tuned cymbals: praise him upon the loud cymbals/Let everything that hath breath: praise the Lord” (150.5–6). Coverdale’s metrical version, with its pronounced central pause, uses the Hebrew two-line structure to echo the sonorous half-lines of Anglo-Saxon verse. More fluid translations draw us into other poetic worlds:

Let ringing timbrels so his honour

sound

Let sounding cymbals so his glory

ring

That in their tunes such melody

be found

As fits the pomp of most

triumphant king

Conclude: by all that air of life

enfold

Let high Jehovah highly be

extolled.

(Mary Sidney, Psalm 150)

So, too, the poetry that made its way into the medieval liturgy, such as the Dies Irae and Stabat Mater, connects us to the inner world of Christ and those who knew him. As Gillhammer notes, “The gospels restrict their laconic narrative to events that can be externally observed. They report what happens and what is spoken as Christ is on the cross, but are mostly silent on the subject of feelings. In every age these blank spaces have been filled by believers’ own imaginations.” No tool is so powerful for this as poetry. At secular funerals, almost all readings are from poetry rather than prose. The medieval liturgy makes full use of both biblical and extrabiblical poetry, in spite of previous Church efforts to exclude the latter (see, for instance, Canon 59 of the Council of Laodicea). Indeed, it makes full use of the whole body, all the senses, the imagination, the power of theater, and almost anything else it can (the major exception being dance). The components of the modern liturgy were only part of a much larger, richer whole.

The Middle Ages would have been very much poorer had the Laodicean attitude been allowed to stand. Today, we are much poorer without the Dies Irae, most of the Psalms, the Mystery Plays, the numerous processions that survive in the Orthodox, Eastern Catholic, and sometimes the Anglican Churches, and so on. Medieval Christians loved good preaching and could listen to a Dominican friar for far longer than even a modern evangelical will listen to a pastor. But almost all forms of modern engagement and evangelization are conducted in prose, or else anchored by it. Talks, books, homilies, reading circles all have their proper place, but not nearly as big or expansive a place as we afford them. I’ve heard thousands of homilies and couldn’t quote a single phrase from any of them (in which, I suspect, I have much in common with your average medieval peasant). The words of poems by Herbert, Yeats, or Eliot come far more easily. The words of the Psalms, the canticles, or the Requiem are with me always.

Image by Richard Mortel, licensed via Creative Commons. Image cropped.