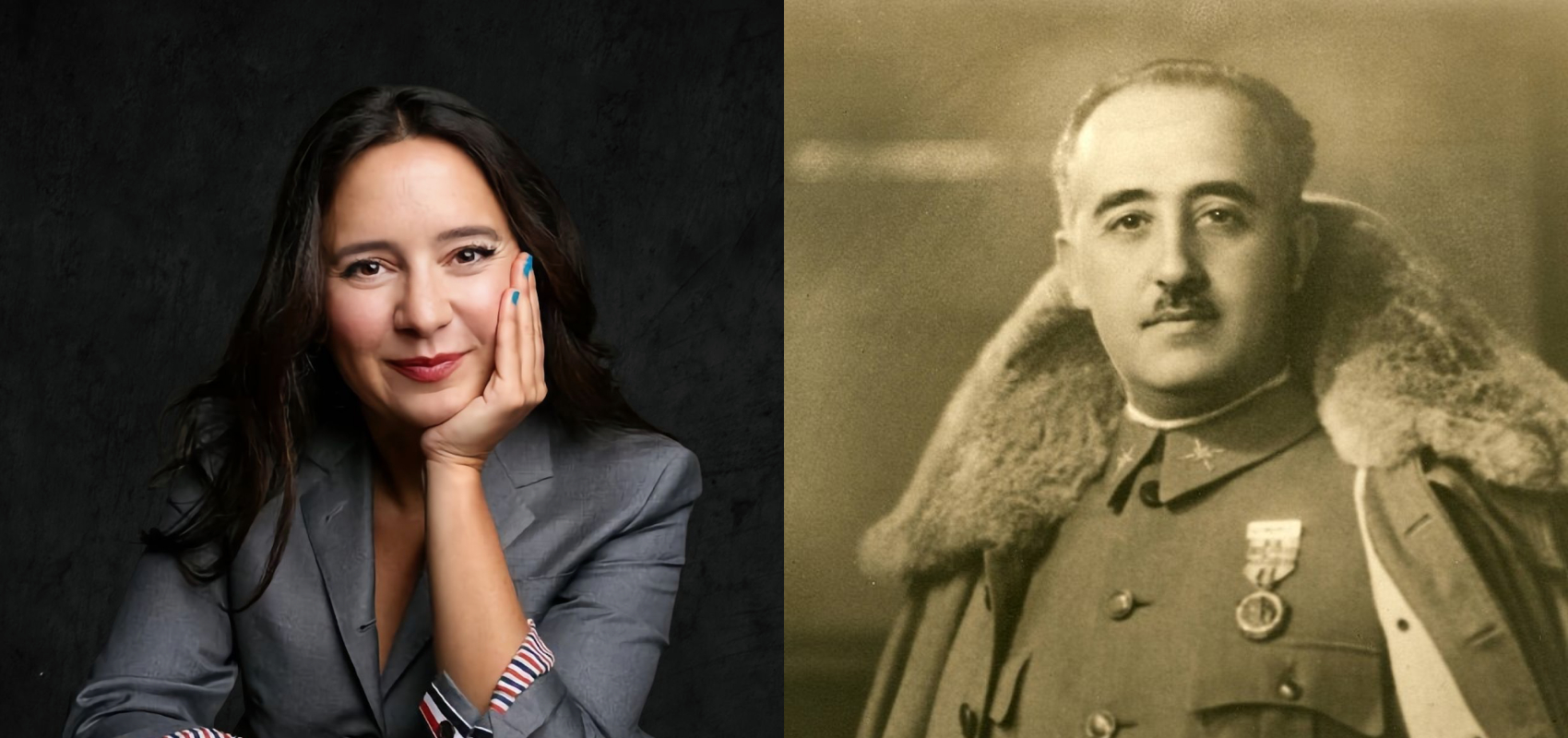

For several years it’s been popular to lament America’s irrevocable slide into the anti-Christian “negative world.” Prognostications of this sort have led some to speculate that, if something doesn’t change soon, a “Protestant Franco” may be inevitable; not because it would be desirable, but because the alternative would be an anti-Christian tyranny. Yet despite how grim things seemed for roughly a decade after Obama endorsed same-sex marriage in May 2012, the astonishing victories conservatives have enjoyed the last few years call into question just how doomed the current order truly is.

Despite the appeal of postliberalism, integralism, and Christian nationalism to many young conservatives, the existence of a populist “silent majority” and an emerging “vital center” of educated professionals opposed to the left should give pause to anyone prophesying a radical rightward shift in U.S. politics. Though the fusionist “dead consensus” that defined the American right for decades is gone, a coalition of traditional Republicans and former leftists, now alienated from the progressive mainstream, is newly possible. No individual so embodies the latter category, the new vital center, as American journalist Bari Weiss, founder of the Free Press and formerly of the New York Times.

Beginning with Dobbs in June 2022, the tenor of American life has shifted right at an astonishing pace. Besides Dobbs, Skrmetti (2025) ensured that red states can categorically outlaw transgender medical procedures on minors, Students for Fair Admissions (2023) effectively put all forms of DEI and affirmative action on notice, and 303 Creative (2023) neutralized the worst threats to freedom of conscience for the foreseeable future. More important than the legal element of these decisions is that they appear to reflect the genuine convictions of not only a majority of Americans, but also a growing plurality of the educated professionals needed for the institution-building necessary to sustain a movement.

Besides these legal victories, recent electoral successes also betray the strength of the (re)emerging center-right coalition. Florida’s Parental Rights in Education Act, also known as the “Don’t Say Gay” law passed in 2022, was a watershed moment, with a number of other states passing or considering similar laws. The law, which prohibits classroom instruction on sexual orientation and gender identity from kindergarten through third grade and restricts it in higher grades, was and remains highly controversial—though there is little chance of it being reversed. While Florida certainly has its share of religious conservatives, the bill would never have passed without broader support.

Even among self-identified centrists—people who a couple of decades ago overwhelmingly voted Democrat—there is support for what can only be described as “public heteronormativity.” When it comes to public institutions like schools, these voters believe heterosexual relationships should be treated as the default. Students at public schools may identify as LGBT, but voters consider it totally inappropriate for schools themselves to influence a student’s sexual or gender identification, even for the sake of combating homophobia and transphobia. That the ban includes even seemingly innocuous references to same-sex relationships made in front of the youngest students is telling; Florida is certainly not banning stories of brave princes rescuing beautiful princesses from third grade classrooms. Voters’ feelings are complex: While they don’t want to be cruel, neither do they want the full consequences of the sexual revolution.

Besides LGBT issues, nothing has done so much to expose fissures between the far-left and the rest of the country than October 7 and its aftermath. Seeing Hamas’s atrocities justified as the understandable result of years of oppression by so many on the left was a turning point for more centrist Democrats.

All political coalitions contain tensions, but in the last decade the fissures dividing the American left have grown so deep that something has had to give. Enter Bari Weiss. No other journalist has so embodied the rightward drift of a significant chunk of formerly blue voters on race, LGBT issues, Israel-Palestine, freedom of conscience, and parental rights in education. On abortion, though pro-choice, she is nowhere near as extreme as the Democratic party now is. That she, as a secular Jew, has come to appreciate so many positions held by conservative Christians is a harbinger of the potential future of coalitional politics in America.

Bearing all this in mind, the right faces two options: a turn toward some form of religious postliberalism, which would necessarily alienate a significant number of “Bari Weiss voters,” or a new “fusion” with former Democrats, newly amenable to conservative arguments. The new fusion would inevitably entail compromise; the Bari Weiss coalition is not likely to accept efforts toward strict abortion regulation, restricting IVF, or overturning Obergefell anytime soon. And yet, given the right’s significant winning streak, it seems plausible that the conservative movement would be better served by working through this emerging coalition.

Much of the rationale for postliberalism has been predicated on the dissolution of America’s identity as a Judeo-Christian nation in even the most nominal terms. As John Adams told us, “Our Constitution was made only for a moral and religious people,” it being “wholly inadequate” for any other kind of people. With this in mind, fears that America could soon be led by communists or reactionaries have been understandable. And yet appeals to values like freedom of conscience, parental rights, meritocracy, and skepticism of utopian projects have returned with a vengeance. It would seem the moral order our Constitution rests upon is not so doomed after all.

The original neoconservatives were made up largely of disaffected Jewish liberals and social democrats associated with City College of New York like Irving Kristol, Nathan Glazer, and Daniel Bell. Though initially inclined toward progressivism, they were driven to the right by the rise of anti-Semitism and anti-Israel sentiment on the left, particularly following the 1973 Yom Kippur War, and disillusionment with statist attempts to solve poverty embodied by Lyndon B. Johnson’s Great Society. Having left the left, these Jewish intellectuals helped form the tip of the spear of a movement that would dominate the right and force the left to adapt for decades.

If it’s true that Donald Trump shares much in common with Richard Nixon, and Joe Biden reprised the role of Jimmy Carter, could Trump’s successor perhaps be the Ronald Reagan of the twenty-first century, able to unite traditional conservatives along with former liberals and leftists in a new “fusion”? The future is never certain, but it wouldn’t be the first time history rhymed.

As with all coalitional politics, religious conservatives stand to gain some and lose some from partnering with Bari Weiss liberals. In one sense, this simply means aiming slightly lower but with a much higher chance of success in order to achieve at least something positive. But on a deeper level, such a fusion would entail purposefully banking on the persuasive power of a kind of natural law, or public reasoning that, without specific reference to theology, nevertheless comports with the moral precepts of a Judeo-Christian worldview. For years it seemed that such reasoning had utterly failed at convincing anyone of anything, as in 2015 when most Americans either shrugged or rejoiced at Obergefell. And yet today, the idea that men and women are intrinsically different and that therefore opposite-sex pairings are different in kind from same-sex ones seems undeniably more persuasive than a decade ago.

If religious conservatives opt for this new fusion, the question is whether they will have a leavening effect on the Bari Weiss coalition or instead themselves become secular in outlook, though with a religious veneer. For the moment, as arguments rooted in the moral coherence of God’s created order seem increasingly persuasive to a broader audience, the former scenario is more likely. We can only pray that, even if these former liberals do not recognize God as the originating moral principle of American society, they will at least acknowledge his laws.