In the summer of 1942, Arthur D. Hyde, vice president in charge of research at General Mills, held what must have been the strangest meeting in his long career as an applied scientist. He had been approached by a young man with connections to the U.S. military seeking a research facility for a team of psychologists. They were developing a novel missile-guidance technique that showed promise in early trials. With fighting raging in Europe, and preparations for the campaign in the Pacific almost complete, this was an opportunity for General Mills to contribute directly to the war effort.

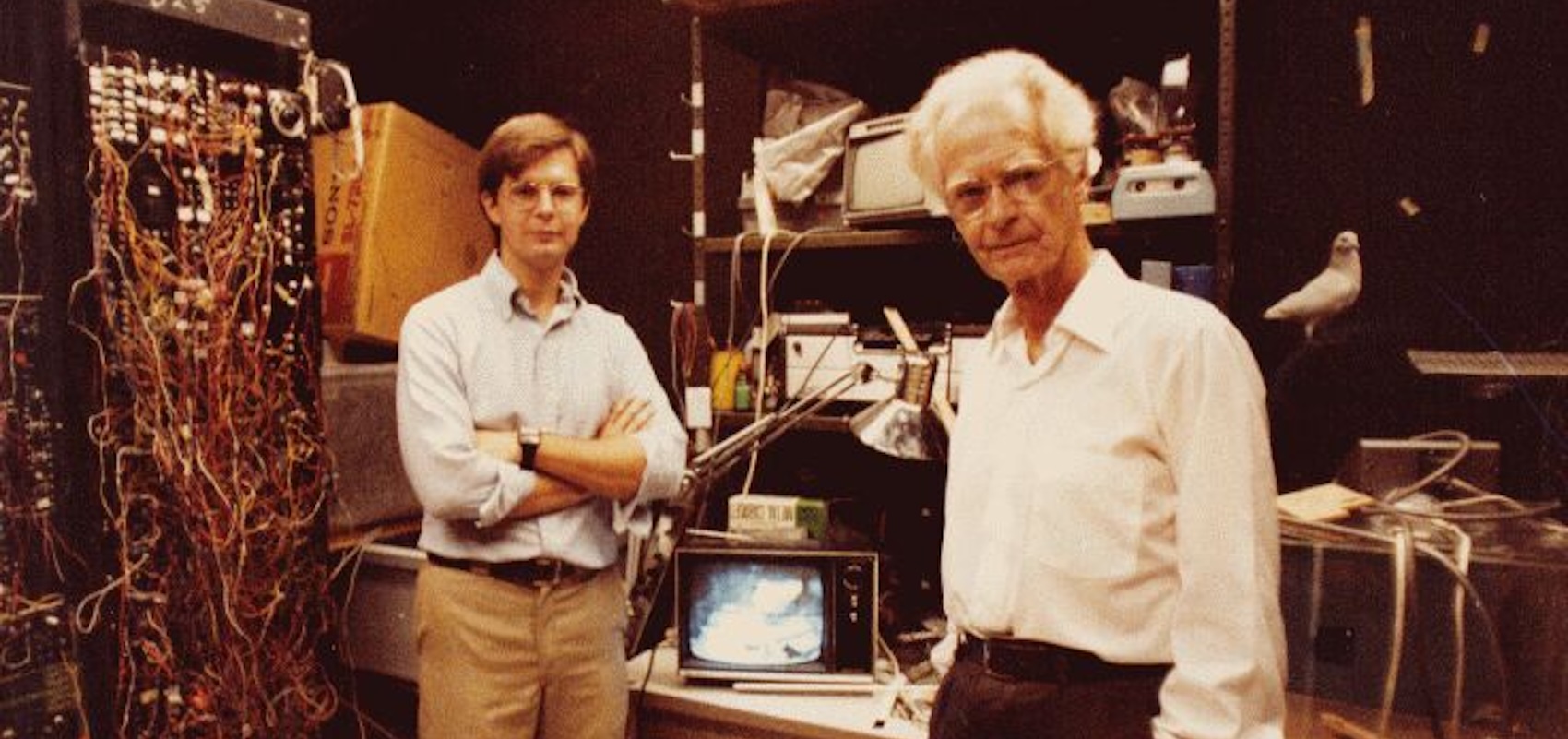

The proposed guidance system, Hyde learned, was not a new piece of machinery but a biological organism trained to act as pilot and bombardier. Burrhus Frederic Skinner, the lead scientist, had demonstrated that pigeons could learn to pick out the visual patterns associated with enemy tanks and planes with remarkable precision. His team had already created a special apparatus to house a pigeon in the nose of a prototype missile. All that was needed to create a potentially war-ending weapon was to find a way to convey the signals from the pigeon to a mechanism that would direct the missile to its target. Concern for the fate of the bird was a peacetime luxury that could not be afforded in an era of total war.

Hyde gave Skinner a laboratory on the upper level of the Gold Medal Flour milling factory in downtown Minneapolis, situated below a sign spelling out the word “Eventually,” an abbreviation of the marketing slogan “Eventually you will use Gold Medal Flour, so why not now?” Had he believed in such things, Skinner would surely have seen in those massive letters a portent or a divine joke. He was then making a name for himself as the leading American proponent of behaviorism, a movement in psychology that emphasized the need for direct empirical analysis of behavior along with skepticism of the explanatory usefulness of mental concepts. For Skinner, notions like “mind,” “volition,” and “intention” were so many psychic fictions that needed to be expunged before psychology could establish itself as a real science. This made him something of an insurgent at a time when the field was still largely understood as the study of human consciousness. He attracted a small group of zealous adherents but a far larger body of equally determined critics. Despite this, he retained an unshakeable faith that reality was on his side and so his position would be vindicated, eventually.

As Skinner found it on leaving Harvard in the mid-1930s, behaviorism was struggling to emerge as a genuine research program. It had been given its name and impetus by the pugnacious John B. Watson, who in 1913 published his manifesto “Psychology as the Behaviorist Views It,” declaring that psychology needed “introspection as little as do the sciences of chemistry and physics.” Though he admired his unflinching materialism, Skinner felt that Watson had issued a promissory note without the results to back it up. The first true demonstration of the possibility of a pure science of behavior, by Skinner’s reckoning, would come a decade later with Ivan Pavlov’s investigations of animal reflexes.

The classic Pavlovian experiments are still widely known today. After gruesome surgical preparation, a dog is restrained and presented with food, and its salivary flow is measured. A “neutral” stimulus such as a metronome beat is then applied each time the food is revealed. Following a number of trials the metronome alone will elicit the same salivary response as the food—evidence of what Pavlov called a “conditioned reflex.”

There is a common misconception that Pavlovian conditioning is, in the memorable words of the psychologist Frank Irwin, all just a matter of “spit and twitches.” Despite his training as a physiologist, Pavlov had no special interest in the functions of the canine salivary system. His real intention was to create a general theory of learning that explained the way behavior is modified by experience in both animals and humans. On the basis of his experiments, he conjectured that learning was reducible to the process observed in his dogs, whereby associations between different stimulus events are formed and reinforced over time. Between the sounding of the metronome and the flow of saliva, there was no need to interpose any “magical explanatory concepts” or “hypothetical mental entities,” to use Skinner’s language.

Pavlov is a star which lights the world, shining down on a vista hitherto unexplored,” wrote H. G. Wells in the New York Times in 1927, read with eager approval by a young Skinner. That light had revealed two surprising facts: first, that learning could be explained in mechanistic terms; second, that the appropriate language with which to describe the mechanism was that of stimulus, response, and reinforcement. Skinner’s own major contribution to the behaviorist movement was to extend this language to include a new form of learning he called “operant conditioning.” The basic operant experiment is described in his first book, The Behavior of Organisms (1938). A pigeon is placed in a box rigged with a lighted button that activates a food dispenser. The box environment, which came to be known as a “Skinner box,” enabled the efficient repetition of experiments with easy control of the relevant variables. Unlike Pavlov’s dog, Skinner’s pigeon is left to learn from the consequences of its behavior as it acts on the environment. Through trial and error it discovers the food-dispensing button, and with each peck a food pellet is released with dependable regularity, acting as a “reinforcer.” Thus, over time, the bird settles into a stable pattern of action, guided by the simple principle that reward is contingent on behavior.

It was during the long summer months in the Gold Medal Flour complex that Skinner had what he later called a day of “great illumination.” Hooking down a pigeon from the laboratory rafters, he attempted to teach it to bowl a small wooden ball. In Skinner’s jargon, bowling is a behavior with a complex “topography” involving a chain of actions performed in a specific sequence. The more complex the behavior, the harder it is to design a reward signal to reinforce it. To overcome this problem, Skinner invented a method called “shaping,” in which the behaviors are built up by a process of successive approximations. Skinner’s team started by reinforcing the pigeon every time it moved near the ball. A further reward was added when it made contact. They continually adjusted the schedule of reinforcement, and in a matter of minutes the ball was “caroming off the walls of the box as if the pigeon had been a champion squash player.”

The team’s members were left staring “at one another in wild surmise.” These remarks have caused some puzzlement among academic psychologists, as Skinner had already performed successful shaping experiments before, most notably with his lab rat Pliny, who was profiled in Life Magazine in 1937. The “illumination” of that day was due to the rapidity with which the bird’s undifferentiated behavior had been molded into complex form with a minimum of stimuli. All that was required to work this miracle was reinforcement learning rigorously applied.

Project Pigeon, as it was known among insiders, was mothballed before the end of the war, leaving Hyde with “a loftful of curiously useless equipment” and a few dozen maladjusted birds. Reflecting on his unsuccessful stint in weapons design, Skinner conceded that the pigeon-guided missile was a “crackpot idea,” but he added that the virtue of such ideas is that they “breed rapidly and their progeny show extraordinary mutations.” With his wartime epiphany still working on his brain, he turned his attention away from pigeons and rats, to the fundamental problem of all psychology: the human mind.

Skinner had previously warned his readers in the last chapter of The Behavior of Organisms that extrapolation from the results of his animal-conditioning experiments to humans was unjustified. But he did allow himself to speculate that the only difference between pigeons and men would lie “in the field of verbal behavior.” In one respect this is not so much a conjecture as the statement of a triviality. After all, humans talk and animals do not. But there is more to the language problem than mere “species-specificity,” as Skinner learned from a chance meeting at Harvard with the philosopher A. N. Whitehead, who challenged him to explain the statement “No black scorpion is falling upon this table” in terms of stimulus and response patterns. Skinner was stumped, and his attempt at an answer satisfied neither himself nor his esteemed guest.

With the end of the war and his return to academic life, he began work on a direct descriptive attack on the language question, which culminated in 1957 with the publication of a major work titled Verbal Behavior. It is a sprawling book, but its central argument can be summarized in a few propositions. The first is that language use is a subclass of behavior, more resembling a pigeon batting a ball than a dog salivating in a Pavlovian experiment. It follows that, like all such behavior, it can be explained in terms of a learning process based on stimulus, response, and reinforcement history. These concepts are defined in the standard way: Stimuli refer to the environmental situation in which behavior is observed, responses are elements of behavior that change in an orderly way over the learning process, and reinforcements are the signals critical to effecting that process. Nothing else is needed and nothing else is admissible without reawakening those “ghosts of dead systems” that Skinner was so keen to exorcise.

What is learned over this process is not knowledge of linguistic structure but “response probabilities,” so that when we receive one set of stimuli we dependably reproduce the expected set of verbal behaviors. Language differs from other forms of behavior only in that all reinforcement comes “through the mediation of other persons,” whose approval acts like the food pellet dispensed to the pigeon. The rest of the book is dedicated to categorizing the different classes of stimuli that drive linguistic behavior. A baroque system of classification emerges, full of strange new terms: “mands,” “tacts,” “echoics,” “intraverbals,” “autoclitics.” What becomes of man under Skinner’s analytical lens has been aptly described by Stephen Winokur: “Man himself has been eliminated as a causal variable; he is just a place where causal variables interact to produce talking.”

Initial reviews were largely positive, with one philosopher of language anticipating that the influence of Skinner’s theories would be “deservedly great.” As it turns out, this prediction was right, but for the wrong reasons. Verbal Behavior did cast a light over the whole territory of psychology—only not the even, stellar light that Wells saw in Pavlov, but the flash and flickering afterglow of a comprehensive demolition.

Two years after the publication of Verbal Behavior, a young professor of linguistics at MIT, Noam Chomsky, filed his own review with the official journal of the Linguistic Society of America. It went on to become one of their most popular articles of all time, presenting what Chomsky intended to be the definitive critique of a “futile tendency in modern speculation about language and mind.” His first line of attack was to invert an argument favored by philosophically sophisticated behaviorists such as Skinner’s friend Willard Quine, who had famously observed that we lack reliable identity criteria for mental states, and stipulated that there can be “no entity without identity.” Quite so, Chomsky argued, and on those grounds stimuli and responses have no existence, either, for they are every bit as vague, evanescent, and impossible to define as mental states.

To this conceptual analysis he added a second line of attack with a more empirical flavor. Chomsky noted that when children learn languages, they acquire the ability both to produce and to recognize meaningful utterances without digesting thousands of examples. It is as if each child had “constructed” a “grammar for himself,” an internal device that allows him to distinguish sentences from non-sentences. The speed with which this grammar is assembled suggests that it is not entirely learned through trial and error, but must be largely innate. This was the first articulation of what would later be called the “poverty of stimulus” problem: We not only learn the verbal behavior to which we are exposed, but very soon in the language-acquisition process, we can freely create a potentially infinite set of sentences.

This argument flows into the final element of Chomsky’s critique: that language use is creative, in the sense of stimulus-independent. This claim has been variously styled by Chomsky the “Cartesian” or “Galilean” challenge, but it might as well have been called the Whiteheadean challenge, as this is precisely the point the canny old philosopher was making with the sentence he put to Skinner when they met at Harvard: “No black scorpion is falling upon this table.” In what way could an absent object act as a stimulus event? And how could such a sentence, about a non-thing not-falling, ever be an output of a stimulus-response mechanism? It was for this reason, as Chomsky would repeatedly argue over his career, that it is impossible to give a mechanistic explanation of language mastery.

Chomsky’s review landed among the behaviorists like a bombshell. Skinner never responded, leaving it to one of his trusted deputies eventually to post a rejoinder. A measure of its impact is given by computer scientist Joseph Goguen, who, arriving at Harvard as an undergraduate shortly after Chomsky issued his critique, recalled thinking that “the handwriting seemed on the wall for Skinner’s brand of extreme reductionist behaviorism.”

And so it seemed. Some time after the dust had settled on the Verbal Behavior debate, with Chomsky’s own theory of generative grammars now the reigning orthodoxy in linguistics, two mathematicians went for a walk through the streets of Santa Fe one winter afternoon. The younger of the two, Gian Carlo Rota, was a colleague of Chomsky’s at MIT. He had become preoccupied with the problem of artificial intelligence, which was going through one of its periodic resurgences in the universities. His companion, Stanislav Ulam, a leading figure in the Manhattan Project, was less enthusiastic. He predicted that nothing would come of the latest round of funding and research, as previous AI frenzies had failed to push the question much beyond where Descartes had left it in the sections of the Discourse on the theory of automata.

“Your friends in AI,” Ulam opined, “still want to build machines that see by imitating cameras. . . . Such an approach is bound to fail, since it starts out with a logical misunderstanding.” More precisely, it was a misunderstanding of the nature of logic itself, which “formalizes only very few of the processes by which we actually think.” Getting to truly intelligent machines would require an extension of the whole domain of logic that had the potential to undermine its own foundations. The decisive discovery would probably have something to do with the logical basis of analogy, which Ulam elsewhere called an “intuitive faculty” of “transcendental value.” That, at least, was his guess, and Ulam was generally acknowledged to have the most accurate guesses in mathematics.

The two agreed to leave the subject to the nascent coalition forming between their colleagues in the computer science and psychology faculties, but Rota continued to puzzle out the strands of their discussion in his head. He wrote later that he wondered, as he walked home through the melting snow, “whether or when AI will ever crash the barrier of meaning.”

Rota died in 1999, in the depths of the last AI winter, his life cut short by undiagnosed heart disease. Had he been exceptionally long-lived he might have seen the barrier of meaning well and truly crashed in 2022, when the new class of large language models (LLMs) was thrust into the public’s hands for the first time. Quite abruptly the seemingly intractable problem of computer language processing appeared to dissolve into thin air.

Rota had said of Ulam that he resembled an Old Testament prophet with a special channel to God’s intentions, but in this instance his vision failed. Today’s AI revolution did not come by way of a deep insight into the special logic of analogy, but through the resurrection of the older behaviorist paradigm, which Chomsky had seemingly destroyed in the 1950s. To adapt a phrase from the legendary AI researcher Seymour Papert, the new language machines are “behaviorism in computer’s clothing.”

When Papert made this statement in the late 1980s, he was referring to the predecessors of current deep learning models developed by David Rumelhart and the connectionist school. It was calculated to provoke Rumelhart, who had been careful to protect his research from imputations of behaviorism, which was still a term of abuse at the time. In Parallel Distributed Processing (1987), he and his coauthors argued that their approach was “antithetical” to Skinnerian behaviorism, as it was based on how the brain acquires “internal representations,” something Skinner dismissed as nonsense. Taking inspiration from contemporary neuroscience, their models were assembled from large arrangements of interacting neuron-like computational units. But as Papert noted, the biological metaphor, though suggestive, conceals a process that is reducible to terms more or less identical to those of classical behaviorism:

Learning takes place by a process that adjusts the weights (strengths of connections) between the units; when the weights are different, activation patterns produced by a given input will be different, and finally, the output (response) to an input (stimulus) will change. This feature gives machines . . . a biological flavour that appeals strongly to the spirit of our times and yet takes very little away from the behaviourist simplicity: although one has to refer to the neuronlike structure in order to build the machine, one thinks only in terms of stimulus, response, and a feedback signal to operate it.

With typical farsightedness, Papert added that a system that was able to “learn whatever is learnable with no innate disposition to acquire particular behaviours” would in itself constitute a “vindication of behaviourism.” Such a machine would demonstrate that stimulus-conditioning is, as Skinner had predicted more than fifty years ago, sufficiently rich to explain language use and just about everything else in the field of behavior.

If the older generation of connectionists found comparisons with Skinner distasteful, current researchers are far happier to own their behaviorist inheritance. Indeed, behaviorism appears to have crashed its Chomsky barrier. In their massive textbook on reinforcement learning, Richard Sutton and Andrew Barto, recent recipients of the Turing Award (often called the Nobel Prize of computer science), discuss how Skinner’s shaping techniques provided the fundamental insight for dealing with the problem of sparse reward, in which the complexity of the desired behavior makes it difficult to design a suitable signal to guide the AI. This is exactly the problem that Skinner faced during Project Pigeon, and which he solved by his method of successive approximation.

One would almost be tempted to call LLMs “Skinner machines,” were it not for the fact that Skinner himself was generally skeptical of the value of computer systems as a research tool. When one of his most gifted graduate students left the behavioral laboratory at Indiana University to work on the theory of computer learning, Skinner naturally assumed that his brain had been damaged by wartime trauma. If not a Skinner machine, then we can follow Geoffrey Hinton, one of the most prominent AI researchers alive today, who has described modern deep-learning models as a virtual system of Skinner boxes.

For his part Chomsky, who is exceptionally long-lived, has conceded that an AI that could do all the things Papert described would partially vindicate the behaviorists, but he contests that this is an appropriate characterization of LLMs. He has doggedly maintained all the elements of his earlier anti-behaviorist critique—though whereas previously they seemed to constitute a knock-down argument, today they have lost much of their potency.

For example, the Cartesian challenge—that language cannot be produced mechanistically—must be substantially revised, and in such a way as to create suspicions of special pleading, given the startling effectiveness of LLMs at generating novel and coherent sentences. As for the inconsistencies Chomsky found in the basic concepts of stimulus, response, and reinforcement, those criticisms can now be dealt with in the way Frank Ramsey once settled Wittgenstein’s concerns about the logical coherence of mathematics: Suppose a contradiction were to be found in the axioms of set theory, do you seriously believe that a bridge would fall down? The language machines, like bridges, are solid facts.

But the “poverty of stimulus” argument has, if anything, been strengthened. All of the models used today require biologically implausible amounts of power and data to be trained. Whatever children do when they learn language, they clearly do not ingest the entirety of all written script stored in the internet. Nor do they consult a vast archive of pre-labelled and carefully curated examples. Evolutionary explanations of how an LLM-style machine could appear in the biological world are likewise non-starters. There is something in the way our intelligence operates that suggests not a vast statistical exercise performed over billions of parameters, but a series of singular and sudden apprehensions. We do not average reality; we grasp it. For those sympathetic to Chomsky, as I am, artificial intelligence is just one more evidence of that wholly mysterious feature of the human intellect: its creativity.

But that is, increasingly, a minority position. Among Skinnerians, language has always been viewed as the last stronghold of “mind.” Artificial intelligence has all but brought that stronghold down, and in doing so has created the conditions for a renaissance in behaviorist thinking. For those who believe in things like mind, ideas, intentions, the good, the true, the beautiful, let this be a warning.

When John Watson launched the behaviorist project, he declared that its final ambition was the “prediction and control of behavior.” Though there is enough variety in behaviorism to frustrate easy generalization, it all finally converges on a picture of the human person as an automaton that can be shaped as readily as a pigeon.

Skinner was one of the few behaviorists who tried to imagine what society would look like if it were designed on operant principles. He did so in two books, the utopian novel Walden Two (1948) and Beyond Freedom and Dignity (1971). Reading them today, one is shocked by their lunatic consistency and terrible emptiness. They also provide surprising insight into our own social arrangements.

For can we honestly deny today that human behavior is to a large degree manipulable? In the West, governments are already experimenting with “nudge units” that design policies on the basis of behavioristic models. In less democratic systems, most famously in China, far grander efforts in social engineering are already underway. But for the modern consumer, the largest flow of conditioning stimuli comes through the large technology companies, which constantly collect data along thousands of dimensions, the better to model and shape the behavior of their users. Stare long enough at a bus full of people tapping away at their phones, and they will quickly come to resemble pigeons in boxes.

Indeed, more and more our society is becoming a sort of box populi, as one of Skinner’s friends memorably described Walden Two, a book that has suffered from being more debated than read. Today it is probably best known for its influence on Anthony Burgess’s A Clockwork Orange and Stanley Kubrick’s film adaptation of that novel. But readers who go to the book expecting to find humans walled up in vast Skinner boxes, half-starved and intermittently electrocuted, will be disappointed. The community at the new Walden pond looks more like a branch of the Amish than like Burgess’s malign conditioners. Skinner tells us plainly that his social program was intended to replace the anarchic conditioning schedules already imposed on humans as consumers and technology users, with a plan better designed to match the needs of the “human organism,” to use his preferred language.

I anticipate that it will become more attractive as the anarchy intensifies. But we must always remind ourselves of the cost, which was worked out by C. S. Lewis in a series of lectures delivered at the University of Durham in 1943, around the time Skinner was exploring the most efficient way to pack pigeons into missiles:

However far they go back, or down, [the conditioners] can find no ground to stand on. . . . It is not that they are bad men. They are not men at all . . . they are artefacts. Man’s final conquest has proved to be the abolition of Man.

Image by Biglicks12 licensed via Creative Commons. Image Cropped.