It’s striking how little turmoil the dawn of AI is causing at top universities across the country. Big Tech companies are moving quickly to embed AI products into every layer of American education. In June of last year, Google announced that it was offering Google Gemini to teens through their school accounts, and the New York Times recently revealed plans by Sam Altman, CEO of OpenAI, to embed ChatGPT into “every facet of campus life.”

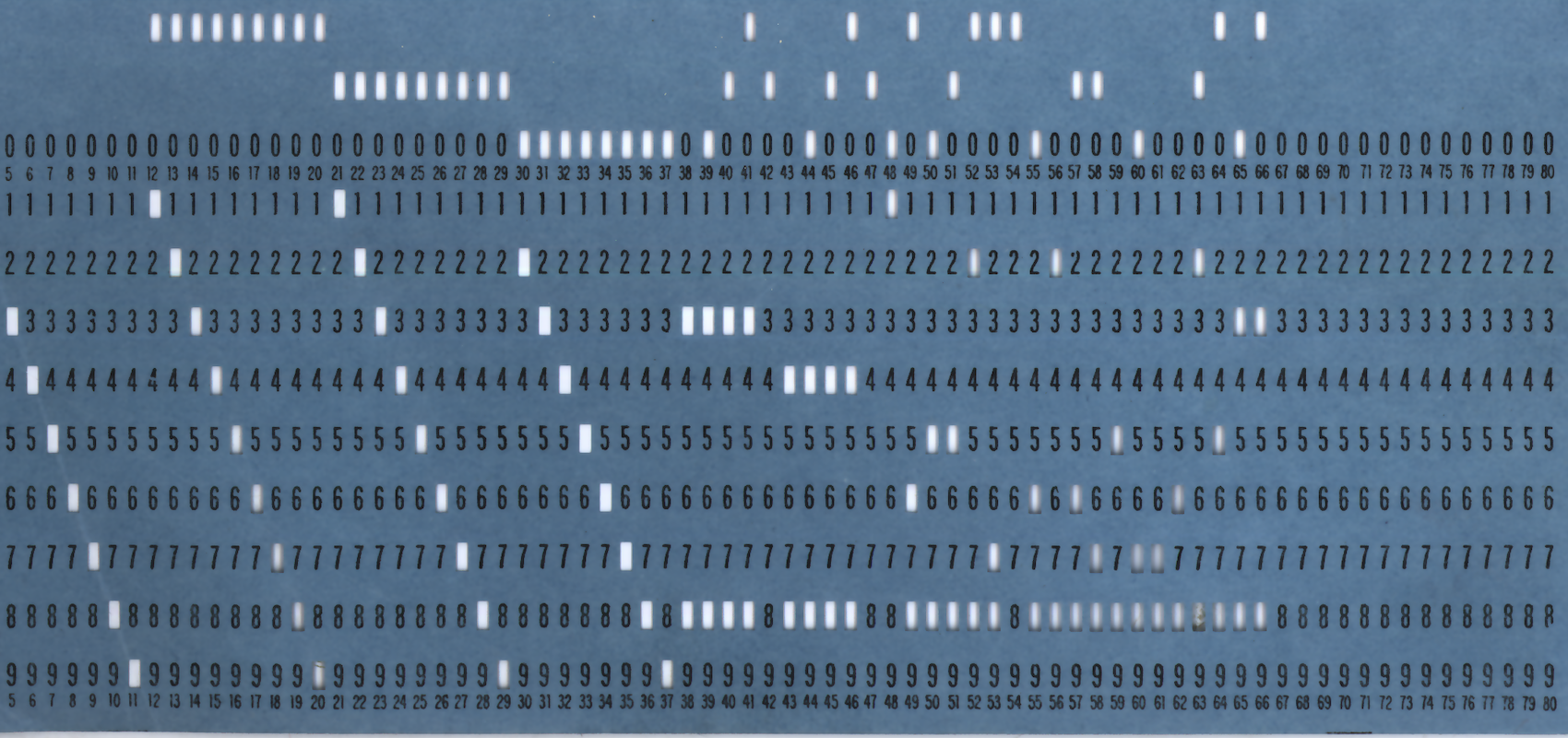

Compare today’s quiescence with the outrage of 1964. Back then, the Free Speech Movement at Berkeley reacted violently to the revelation that a university laboratory was operating an IBM computer, which was seen then as the manifestation of all things bureaucratic, corporate, and technological—the antithesis of free learning. (This was before the ideology of the PC, with its utopian vision of the computer as an anti-bureaucratic, liberating force.) Graduates and undergraduates protested by burning IBM punch cards, which, back then, supplied the computer with commands and were used to register students for classes. Graduate student and movement leader Mario Savio’s famous speech recalls the anti-technology element of the student protests, which we have largely forgotten:

There is a time when the operation of the machine becomes so odious, makes you so sick at heart, that you can’t take part; you can’t even passively take part, and you’ve got to put your bodies upon the gears and upon the wheels, upon the levers, upon all the apparatus, and you’ve got to make it stop. And you’ve got to indicate to the people who run it, to the people who own it, that unless you’re free, the machine will be prevented from working at all!

To the student radicals, the IBM card was the symbol of a rotten university and a cultural “system” that was threatening to turn them into machines. Savio cried: “We are human beings!”

Today, if elite universities are worried about how large language models (LLMs) will affect education, there is little sign of it. AI has made it clearer than ever that the project of cultivating a literate and humane elite is dead, and the academy seems disinterested in the danger of permitting man to outsource his highest faculties: thought and speech.

A few professors have sought to check the total encroachment of generative AI by re-introducing oral examinations and requiring essays to be written in class without the aid of computers. But the general attitude is one of accommodation. In practice, this entails redesigning home and classroom work to give LLMs primacy of place. An already-typical assignment—as one professor at a top university recently told me—is something like, “Prompt ChatGPT to construct the essay’s outline, have it write the first draft of the essay, and then personally edit, fact check, and finalize it for submission.” Or, “Write something of your own on a given topic, then prompt ChatGPT to generate a parallel text on the same subject, and check your work against it.” The idea being that—despite ample evidence that generative AI models are bona fide liars—they can show students where they come up short, both in knowledge and craftsmanship as writers.

Professors rationalize their welcoming of AI by citing its near-certain use in a professional setting. Words will no longer be the work of human beings, professors have concluded, so it would be disadvantageous for their students to waste their time practicing to read and write with rigor independent of the LLMs. Students won’t have need for words or thoughts of their own in the workplace—all of these will come from ChatGPT. By ceding the burden of literacy to the AI, they are preparing students for how they will spend the rest of their lives. This is a tacit admission that the value of words is derived principally from their usefulness to American business.

Words themselves are being automated and relegated to corporate tools and commodities. Generally speaking, automation is a process in which a private company—or the state—applies technology and managerial techniques to reduce the role of human beings in activities that formerly belonged to them alone. In Capital Book I, Marx writes about how machinery was introduced in manufacturing, displacing the human worker and making him subservient to the machine. Marx says,

In handicrafts and manufacture, the worker makes use of a tool; in the factory, the machine makes use of him. There the movements of the instrument of labour proceed from him, here it is the movements of the machine that he must follow. In manufacture the workers are parts of a living mechanism. In the factory we have a lifeless mechanism which is independent of the workers, who are incorporated into it as its living appendages.

This diagnosis applies to our present crisis. The current question of automation has focused on work and the fear that AI and robotics will cause skyrocketing unemployment. That fear is not misplaced. Yet, it is still not the deepest threat that artificial intelligence holds for our self-understanding and role as human beings. In the work of locution, articulation, and conceptualization, humans are being moved to the side and replaced by the “lifeless mechanism” of AI into which the minds of workers will be incorporated as “appendages.”

The mechanization of craft and muscle power convulsed the West in the nineteenth century, pitting class against class, spurring revolutionary violence, and toppling governments. But the mechanization of the mind will have deeper effects on human beings and human society. Plato and Aristotle, and the entire classical tradition, recognized the mind as the highest element of the human person. It is that which separates us from brutes.

If the project of automating the mind is completed, then the line between man and beast will become fundamentally blurred. University professors, at that point, will have but one choice to make: to serve the lifeless mechanism, or teach their students to cry, “We are human beings!”