Andy Warhol’s reproductions of popular brand logos have sparked debate as to whether he is playfully critiquing consumerism or snarkily endorsing it. Similarly, the subject of Warhol’s Catholic faith has fed the debate about where to draw the line between sincere and performative belief. But perhaps his faith had more influence over his art than his critics realize, allowing Christ to shine through even the quotidian soup can.

Few have managed to engage both aspects of Warhol’s legacy—his pop art and his faith—with as much nuance as French theorist Jean Baudrillard. Though a non-believer, Baudrillard was one of the few theorists capable of grappling with the religious implications of both postmodernism and consumerism. Despite his nihilistic tendencies, Baudrillard’s insights into Warhol’s oeuvre challenge believers to look more closely at its religious dimensions.

Enchantment is a scarce resource in the age of brand power. Yet Baudrillard insists that it has not disappeared altogether; rather, it has merely been transferred. When an object becomes a brand—an “icon”—it takes on a quasi-sacred aura. Eating Campbell’s tomato soup may be a humdrum experience, but hanging one of Warhol’s Campbell Soup can prints is a magical experience. Thus pop art takes consumerism to its “exponential, ecstatic extreme” in its “ironic, transparent simulation of the real.”

Indeed, Baudrillard sees something “heroic” in Warhol’s ironic self-awareness. “Where others seek to add a little soul, Warhol adds a little more machinery. Where others seek a little more meaning, he seeks a little more artifice,” he said in Absolute Merchandise. And so, “By employing just a touch more simulation and artificiality, Warhol out-maneuvers the very machinations of this system,” reaching “the machine’s magical core by reproducing the world in all its trite exactness.”

Yet Baudrillard is skeptical that Warhol actually subverts the hold of mass media and major corporations: Warhol’s “knowing wink,” his “‘cool’ smile of humor . . . is not the smile of critical distance, but the smile of collusion,” Baudrillard wrote in The Consumer Society. His ironic critique of commercialism is ultimately “complicit,” as it is incapable of slipping away from the all-encompassing grasp of its tentacles. Ultimately, the pop artist inevitably “runs up against a sociological and cultural status of art which they are powerless to change.”

Baudrillard couldn’t see the meaning in Warhol’s art because he believed consumerism cuts off access to meaning. Warhol gets no help from a nihilist, and neither does he receive recognition from fellow believers, who tend to dismiss his Catholic faith as a mere cultural appendage or an affinity for kitsch and aestheticism. And while there are others who have come to the defense of Warhol’s religiosity (as “bad” as it may have been), most settle for sentimental appraisals of his faith.

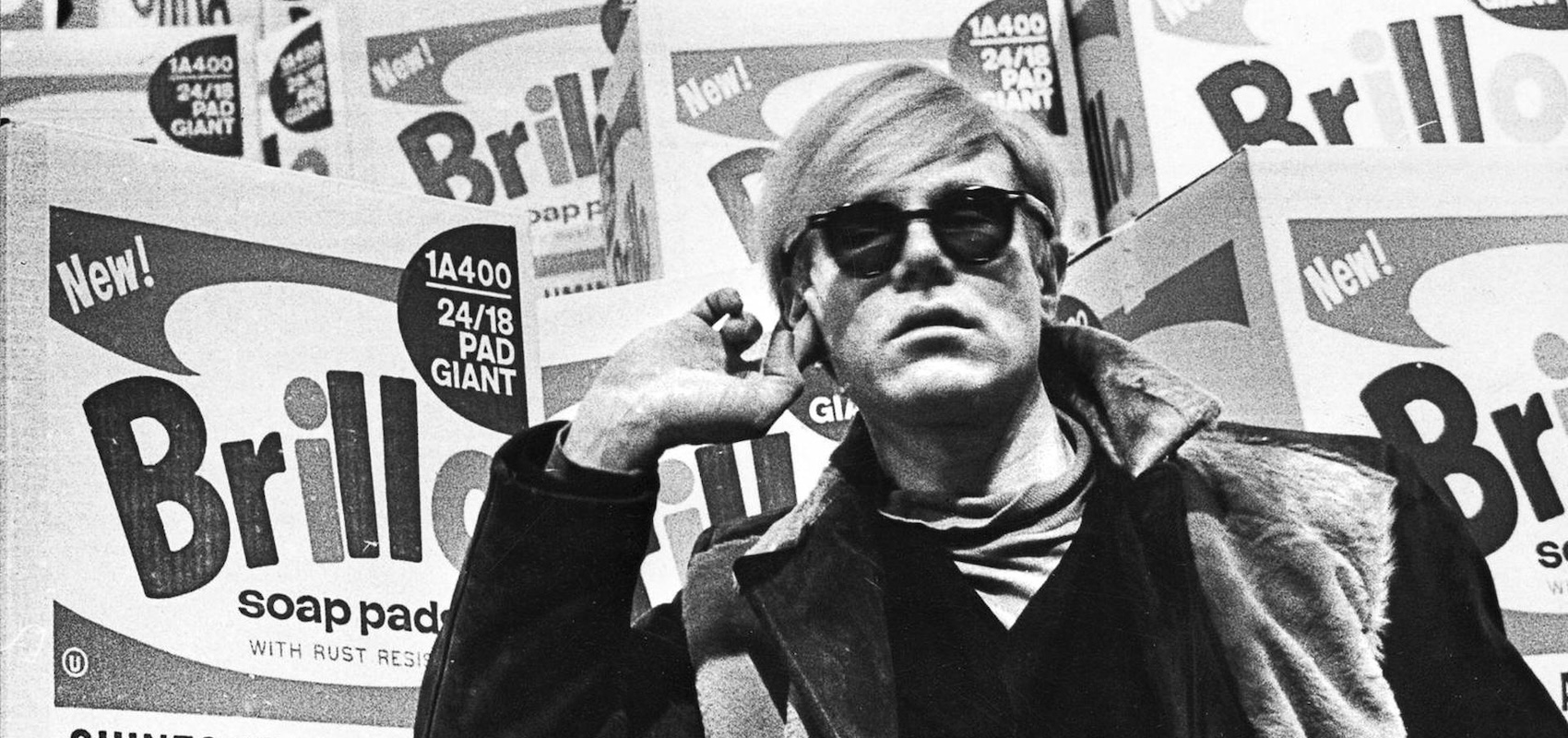

But neither his nihilistic nor his religious critics are correct. Warhol’s work contains a religious genius that lies precisely in his ironic “collusion” with consumerism. Warhol, unlike Baudrillard, was not a nihilist. He believed in a transcendent deity who would turn bread and wine into his own body and blood. Surely that same God could also bestow some sacramental value on mundane realities like a soup can, a Brillo pad, a banana, and a gunshot wound. His works that juxtapose product packaging with religious imagery are tinged with the awareness that Christ’s love can redeem both human weakness and the banality of the everyday (see Last Supper/Be Somebody With a Body, The Last Supper (Dove), and Raphael Madonna-$6.99). This is apparent even in his reproductions of brand logos. Not only are the logos aesthetic in their own right, they often reflect meaningful experiences Warhol had with the brands; the Campbell Soup can reproductions were inspired by his mother feeding him the soup as a sick child, under the watchful gaze of an image of the Last Supper that sat above the kitchen table.

Warhol’s autobiography is imbued with a eucharistic consciousness that turns the most mundane realities (often food) into a gift. Once, when preparing a steak, he changed his mind at the last minute, opting instead for his preferred snack of toast with jam. He left the steak for his neighbor’s cat. On another occasion, he picked up the phone and, on an impulse, “dropped the receiver and ran into the kitchen for some toast with jam.” Each second of his snack break was a divine delight: “While I waited for the toast to toast I read the label on the jar of jam. I took the jar back with me to the phone because I like to spoon it out onto the toast, glob by glob, bite by bite.”

Even something as simple as a Coca-Cola held sacred meaning for him: “A coke is a coke and no amount of money can get you a better coke than the one the bum on the corner is drinking.” For Warhol, food’s sacredness traversed these playful moments and more solemn ones, like when serving food to the homeless at the Church of the Heavenly Rest on the Upper East Side, or while kneeling in front of the Eucharist—which he humbly abstained from receiving—during Mass at St. Vincent Ferrer.

In the debut single from her Warhol-inspired album Artpop, Lady Gaga sings that she “live[s] for the applause.” The singer’s honest admission calls to mind Cardinal Ratzinger’s warning that applauding “human achievement” during the Mass “is a sure sign that the essence of liturgy has totally disappeared and been replaced by a kind of religious entertainment,” which “cannot compete in the market of leisure pursuits.” Warhol issued prophetic warnings not so unlike those of Ratzinger, but from inside “the market of leisure pursuits” that deific figures like Lady Gaga occupy. Take his Marilyn Diptych, which comments on the ephemeral nature of the cult of celebrity. Or his assertion that if you become famous, “they will give you tremendous applause even when you are actually pooping,” which expresses—albeit in his own distinctive tone—a sentiment about the futility of divinizing human accomplishments not far off from Ratzinger’s.

And herein lies the success of Warhol’s subversion. Baudrillard is right to say that Warhol’s use of irony did not fully distance him from the consumer culture he presumed to critique. Rather, it was his openness to God’s grace, precisely within the temple to the false gods of consumerism and artifice, that enabled him to subvert their message from the inside. He coded divine truths in a language that our idolatrous culture could comprehend. Warhol may not have been a paragon of sanctity, but his work was receptive to divine grace. He knew that he who is more powerful than any corporate entity can reach even our disenchanted, artificial age, if only we crack open the door to him.