It might be the Old Testament, but it’s certainly inspiring a lot of new books. Here are four volumes that came across my desk during the last month.

A book arrived this week, a heavy lift at 842 pages, Mark Gerson’s God Was Right: How Modern Social Science Proves the Torah Is True. The book fits with other studies I’ve seen arguing that modern science is fully consonant with Biblical verities. The Torah is “a true and practical guidebook of eternal relevance—for everyone,” Gerson says, and he proceeds to apply the guidance to some fifty contemporary situations. Each one of the latter is paired with an episode from scripture. The kidnapping of Patty Hearst and the phenomenon of Stockholm Syndrome, in which captives develop a fondness for their captors, go with the Jews in the desert who, a year after the Exodus “yearned to return to [their] captors and slave masters.”

The Torah also teaches about our relationship with time. For example, God commanding Lot and his wife not to look back at Sodom is a lesson in leaving a sinful past behind rather than dwelling on it. Gerson relates this to the famous “marshmallow test,” which tests children’s ability to delay gratification and thereby the subjects’ understanding of their own futures. Other social science elements come up, including negativity bias, peer pressure, impostor syndrome, and cognitive behavioral therapy. So do Moses, Aaron, Abraham, Noah, Jacob, the Commandments, Isaac and Rebecca, and the Tower of Babel. The prose is breezy, the illustrations engaging, and Gerson’s conclusion on government corruption (in Exodus 23:8, God says, “You shall not take a bribe”) could not be more timely in light of what DOGE has uncovered.

In Sirach, by André Villeneuve, we have another Biblical topic: one of the deuterocanonical books in the Catholic Bible. The author of Sirach was Ben Sira, a pious Jew in Jerusalem in the second century before Christ, who wrote the work as something of a defense of Judaism in a time of aggressive Hellenization in the region. The work resembles Proverbs in that it is “a compilation of wisdom texts intended to serve as a handbook of moral behavior,” Villeneuve writes. He provides an introduction to Sirach’s historical contexts, a discussion of canonicity questions, and an outline of the text itself before getting to the bulk of the book, which is a detailed and readable commentary on each chapter and verse from beginning to end. The themes range from the personal (“self-control over thoughts, words, and deeds”) to the collective (“prayer for national deliverance”). For teachers of scripture who wish to bring Sirach into their syllabus, this is a worthy exposition.

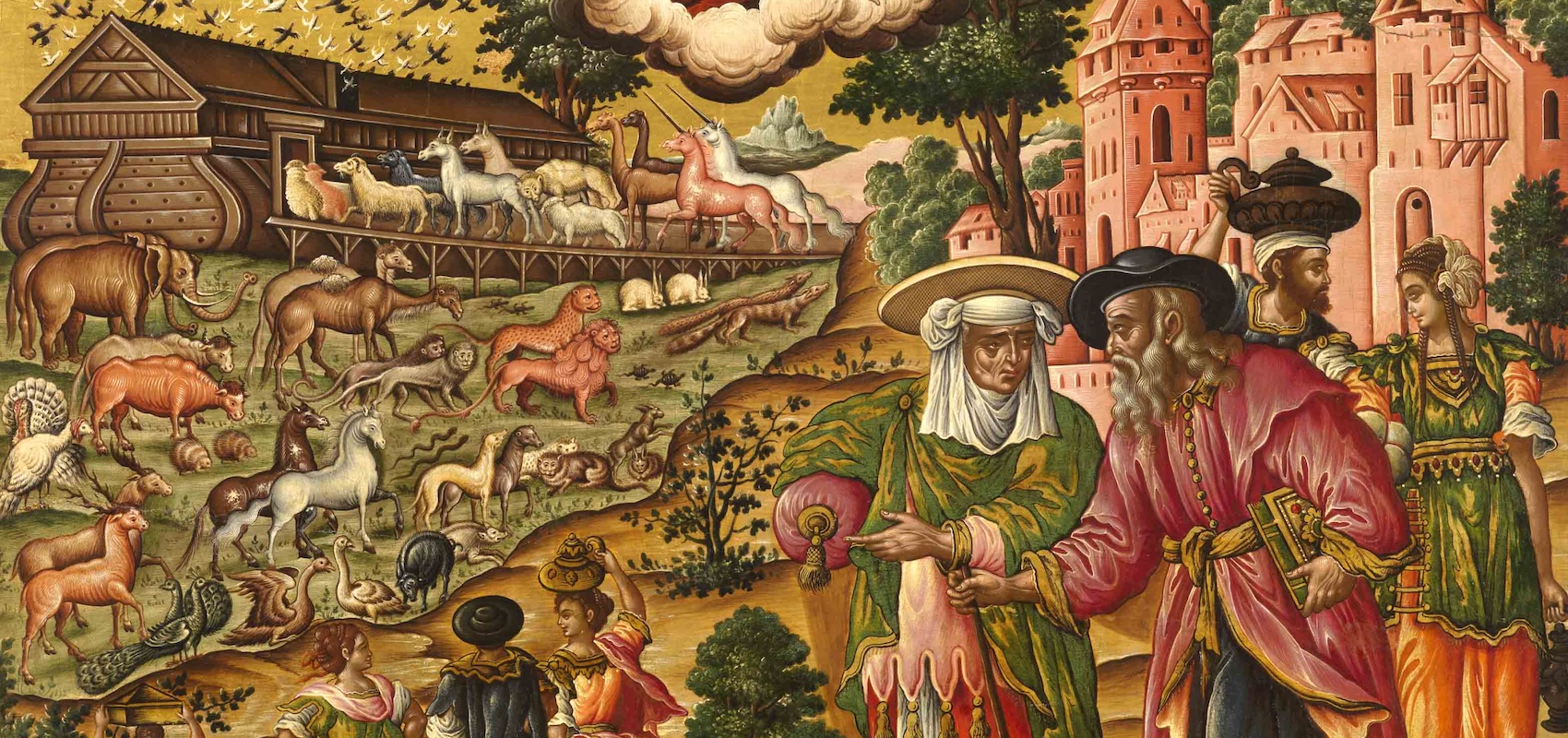

Here is another study of a less obscure topic: Noah and the Flood in Western Thought, by Philip C. Almond. It’s a work of cultural history, not theology, tracing the flood over the centuries and concluding “there are many meanings to the story of Noah to be found within the history of the attempts to interpret it.” There are “flood traditions” in the ancient world to be considered, elaborations on Noah’s significance under Hellenistic Judaism by Josephus and Philo, the “spiritual meaning” of Noah ascribed by early Christians, and what scientists and scholars from the Enlightenment forward did with the tale—for instance, trying to figure how Noah’s descendants ever made it to the American continent. Geologists wondered if a fissure opened in the Earth’s crust and released the waters, while cometologists speculated that a comet did the work (and tilted the axis of the Earth, too). We take a tour of Ark Encounter as well, a museum in Williamstown, Kentucky that has a 510-foot-long replica of the ark: “The world’s largest free-standing timber structure,” Almond notes. You get the picture. This is a fascinating scholarly survey of the episode over time—and it’s fun, too.

One last work to mention, not on the Old Testament, but a work with a close historic authority: The Essential City of God: A Reader and Commentary, by Gregory W. Lee. The book serves as “a guide for readers new to Augustine’s work.” Lee lays out the structure of Augustine’s book, adds historical summaries, and includes an abridged version of the book itself. He fills it out with explanatory notes and essays on angels and demons, the Eucharist, slavery, Platonism, Original Sin, and other issues (some co-authored). The commentaries are keyed to new readers, as Lee says, and his discussions of Christian ideas and practices are, too. This edition might be especially useful in undergraduate courses in early Christian theology, or in any course in which City of God is assigned.